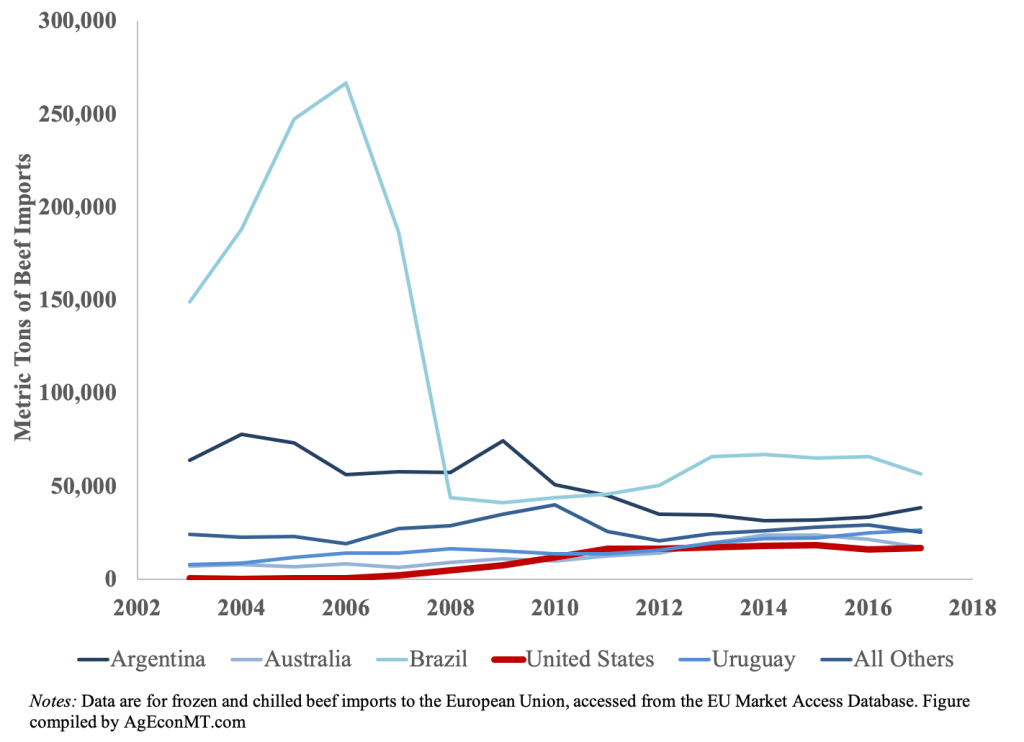

The United States produces, arguably, some of the highest quality beef in the world. Countries in the European Union have some of the highest per capita income and spend some of the highest amount of money on their food. The natural link, it seems, is that the EU should be importing a lot of U.S. beef. But, as the figure below shows, while the United States is one of the top five importers of frozen and chilled beef into the EU, it is certainly outpaced by many of its primary competitors.

One of the reasons for this apparent competitive lag is the events of policy enacted by the EU in the early 1990s. During this period, the European Union introduced a restriction on all imported beef from animals treated with growth-promoting hormones. The ban was the result of consumer concerns about the role of mad cow disease on food safety. As shown in the graph above, this initial policy essentially eliminated U.S. beef exports to the EU. However, because there was a lack of scientific evidence to support the association between hormone-treatment and food safety, the World Trade Organization (WTO) ruled against the EU (and in favor of Canada and the United States) in 1998. That decision allowed the United States to place retaliatory tariffs on EU goods.

In 2009, as a path toward lowering trade restrictions, the United States and the European Union agreed on a memorandum of understanding (MOU). The MOU would initiate a three-phase process for allowing U.S. beef to be imported into the EU in exchange for lower U.S. import tariffs on EU products.

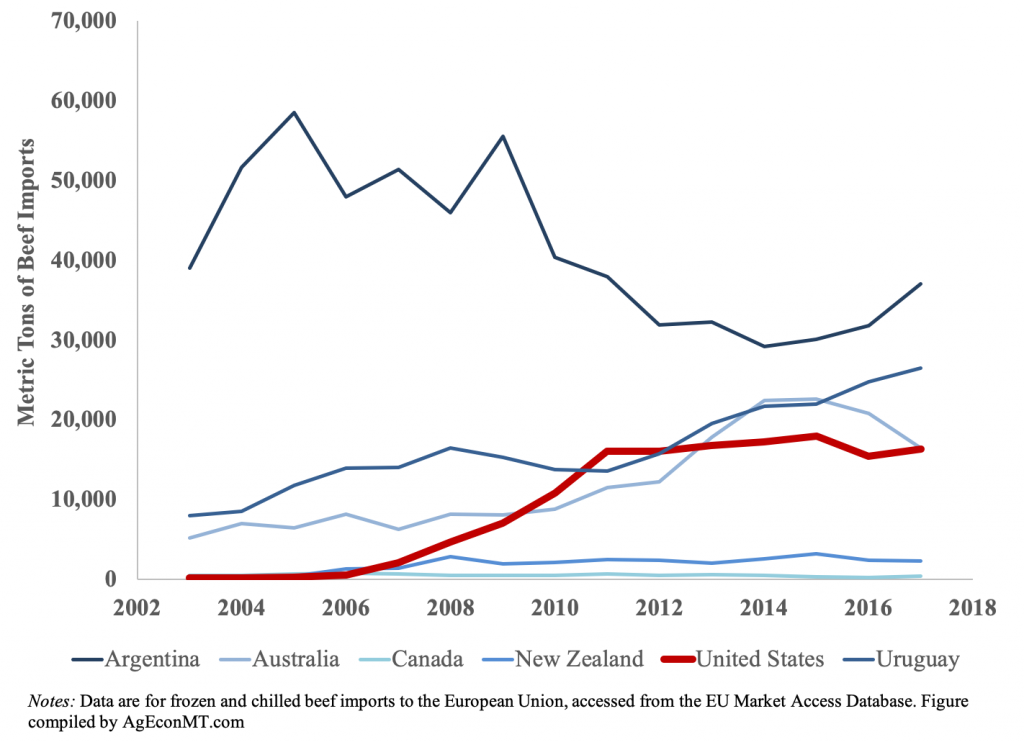

During phase I (2009-2011), the United States could export up to 20,000 metric tons of beef from cattle that were not treated with growth-promoting hormones. After the initial 20,000 tariff-free metric tons, a tariff would be applied. (Such a “tariff rate quota” essentially limits U.S. exports to the tariff-free portion—the 20,000 tons—because the tariff amount on the additional imports would make the costs of those sales exceed the revenues). In the second (2012) and third (2013 and forward) phases of process, the tariff-free quota would be raised to 45,000 metric tons, and the United States would suspend and not apply additional tariffs on EU products.

However, as the figure below shows, despite imports of U.S. beef into the European Union increasing, they never reached the 45,000 metric ton volume. A major reason for this is that when the EU–US MOU was established, other major beef exporting countries cried foul: How can the EU be giving preferential treatment to the United States but not its other trade partners? As a result, the European Union opened up the 45,000 metric ton tariff rate quota agreement to other countries, such as Argentina, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Uruguay. That is, the EU said: We’re allowing a total of 45,000 metric tons of beef imports without tariffs, but all the exporters can fight amongst themselves to determine who gets different portions of this total tariff-free amount.

Allowing this type of competition for tariff-free beef imports has essentially placed a ceiling on the U.S. portion of exports to the EU. As the figure above shows, U.S. beef exports to the EU has consistently averaged around 16,500 metric tons per year, less than half of what the original MOU discussed. In response, the U.S. Trade Representative’s office under the Obama administration began the process of determining what retaliatory actions it could employ under the original 1998 WTO ruling, because, they argued, the EU were not complying to the 2009 Memorandum of Understanding by allowing other countries to participate in the 45,000 ton tariff rate quota. The Trump administration has continued this process.

In mid-March 2019, the EU and U.S. governments reached a deal in principle to provide exclusive rights to U.S. beef producers to export up to 35,000 metric tons of beef certified as being without growth-promoting hormones. While this agreement still needs to get approved by each of the nations within the European Union, historical trade data (shown in the figure above) suggests that barriers to U.S. beef imports were binding. Removing these barriers could more-than-double!

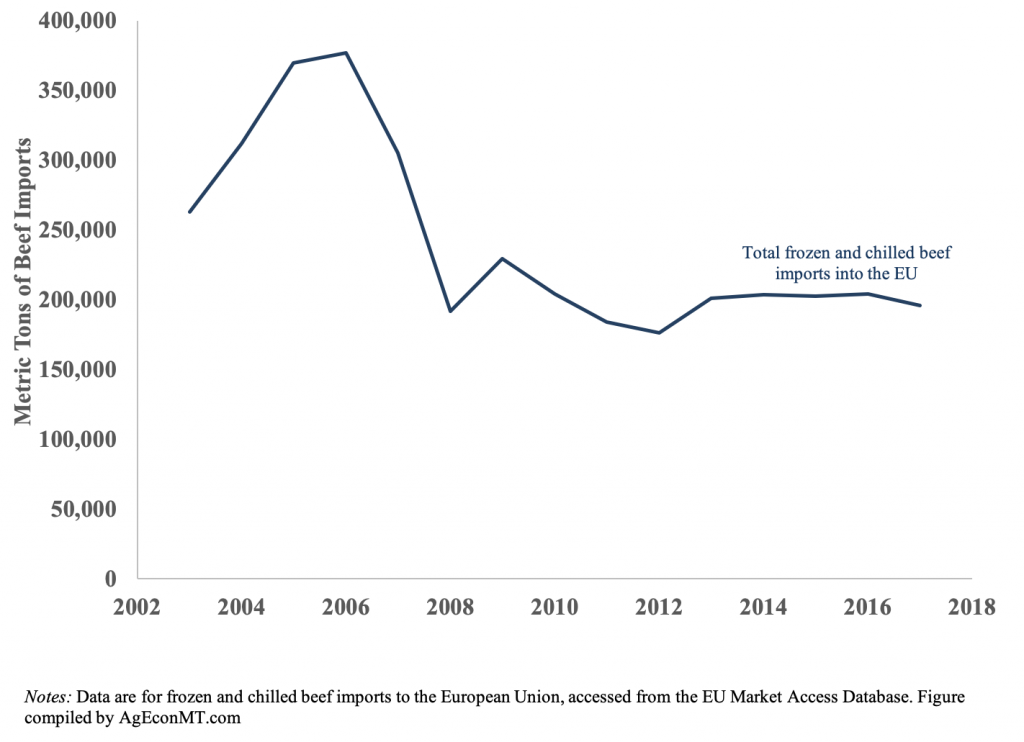

A secondary, but perhaps more interesting consequence of this new agreement, could be the additional market power that the United States beef exporters could gain within the European Union. The figure below shows total beef imports into the EU. Since 2008, the total imports have remained relatively constant (even more so since 2013). This suggests that if U.S. beef exporters increase their sales in the EU and little else changes with European beef production and consumption behaviors, then U.S. beef would potentially crowd out beef imports from its major competitors.

Is your product headed to the EU? Have you been affected by the disputed EU–US MOU? Do you see the EU market as a growing or potential new outlet for your products?

(Photo by usdanrcstexas is licensed under CC BY 4.0)