Organic food is becoming ubiquitous in our grocery stores. While organic products make up a significant share of what’s for sale at “natural” foods stores such as Whole Foods Markets, organic products are widely available at mainstream grocery sellers like Safeway, Walmart, and my local Bozeman grocery, Town and Country Foods. Given the proliferation of organic products, one might assume more US farmland is being converted to organic to fill our grocery shelves.

To find out, I looked at the Certified Organic survey conducted by the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). This survey is likely the most comprehensive publicly available data source on organic agriculture in the United States. In mid-September of 2016, NASS released the results of its 2015 survey of organic farms, providing measures of the number of organic farms, the value of organic production, and the number of certified organic acres. The 2015 numbers can be compared to similar NASS survey data from 2008, 2011, and 2014 (see note on data below).

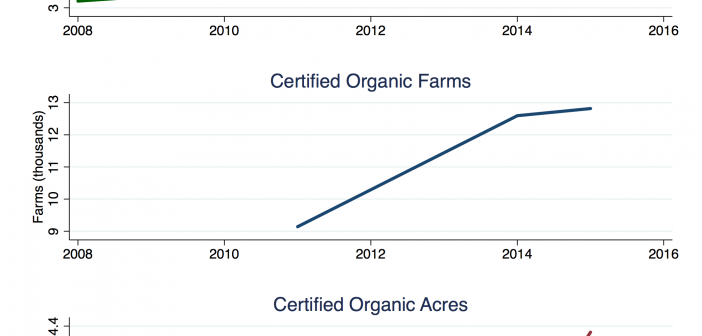

What’s happened to US organic acreage?

Certified organic acres (shown in the bottom graph) grew slowly between 2011 and 2014 before jumping by 20% between 2014 and 2015. In contrast, the number of farms and the value of production increased steadily. Digging into the state-by-state acreage data, it becomes clear that the acreage increase was driven by a change in one very unexpected place.

Nearly the entire national increase in certified organic land of 718,916 acres between 2014 to 2015 came from the state of Alaska. Digging further, as Politico reporter Jenny Hopkinson did, revealed that this increase came from one ranch. Bering Pacific Ranches, a cattle operation in the Aleutian islands, was certified organic in 2015, increasing organic acres in that state from 282 to 695,186. Some farm publications trumpeted the 20% national organic acreage increase without noting its source.

Excluding this major outlier, organic acreage was essentially flat between 2011 and 2015, even as the value of organic production continued to grow and the number of certified farms rose. By some indications, projected profits from organic agriculture are greater on a per-acre basis than for conventional production. For example, Iowa State University enterprise budgets for corn production in 2016 estimated a profit of $6.89/bushel for organic corn production and $0.20/bushel loss for conventional corn in a corn-soy rotation. If organic agriculture is truly substantially more profitable, this presents a puzzle for agricultural economists: why aren’t farmers converting more land to organics?

Possible explanations for the lack of US organic acreage growth

There are a number of possible explanations for why organic acreage has not grown in the United States. I’ve compiled an almost certainly incomplete list:

- Mismeasured profitability: Enterprise budgets may not capture all aspects of farm profitability. Organic farmers may lower costs by not applying synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, but their per-acre labor costs are almost certainly higher. Labor costs may not appear on the farm’s income statement if the farm owner performs this labor.

- Risk: Profits in organic agriculture may be greater than conventional, but also more variable. If farmers are risk-averse, they won’t convert unless the benefits of conversion outweigh the additional risk assumed.

- International trade: organic production may not grow in the US if consumers have access to affordable imports of organic products from other countries.

- Conversion costs: Farms converting to organic incur additional costs during the three-year conversion period. Foregone income, record-keeping, and other costs related to switching production systems are not trivial. These costs may be greater than the price premium for organics in terms of their net present value to the farm.

- Scale inefficiencies: Organic farms may not be able to capture the same economies of scale as conventional farms and so may not have the same incentives to increase in size.

- Intensification: Organic farms are growing, just not in terms of acres. Farms are growing on the intensive margin by producing more output per acre, rather than the extensive margin by adding more acres.

- Government policy: US farm bill programs like crop insurance may favor conventional agriculture

- Credit constraints: Agricultural lenders won’t collateralize certification. Farms cannot extract value from certification to access additional credit or other resources.

Solving this economic puzzle likely requires some careful research to confirm or disprove these hypotheses. It’s likely that more than one of the reasons listed above explains what we are seeing. If you have thoughts about why organic acreage isn’t growing, I’m all ears. Please share in comments or contact me directly.

NOTE: The 2008 NASS Organic survey combines certified and exempt farms and acres. This makes it difficult to compare data from this and later surveys. Not all organic production is certified – farms with less than $5,000 in organic sales are exempt from certification. This makes some economic sense. There’s little point in certifying a farm if the costs of certification are as large or larger than the value of the production being certified. Exempt farms may still sell their production as organic. Depending on your perspective, this is either efficient or a loophole.

(Photo by Damanhur, Federation of Communities is licensed under CC BY 4.0)