Last August Northwestern Energy, Montana’s largest electricity supplier, released an “Electricity Supply Resource Procurement Plan,” which details how it plans to obtain adequate electricity capacity through 2025. The document has proven controversial, stating that the company plans to add 800 megawatts of capacity mainly through purchases of natural gas resources rather than renewable sources like wind and solar. Climate activists staged a protest outside of a recent listening session regarding the plan in Helena.

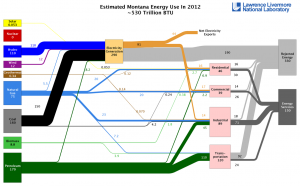

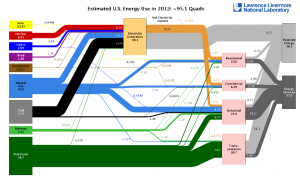

Montana is a mixed bag when it comes to clean sources of electricity. On the one hand, Montana gets a high percentage of its energy from coal relative to the US as a whole, and coal is by any measure the dirtiest energy source. On the other hand, like its neighbors Oregon and Washington, Montana gets a very high percentage of electricity from carbon-free hydroelectric power thanks to the region’s extensive water flow. This is illustrated in “Energy Flow” charts from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory below (note that these are somewhat out of date as the only state-level charts are from 2012). These charts show the volume of energy use from nine different sources, and where that energy ultimately goes. There is a lot of information in these charts, but here I am just focusing on electricity generation by energy source (the top middle part of the graph). Montana gets nearly 100% of electricity from coal and hydro, while the rest of the county gets a good chunk from nuclear and natural gas as well.

Montana’s population and electricity demand are growing rapidly, and unfortunately the scope to further expand the state’s hydropower is limited, since there are only so many rivers and streams available to dam, and these are also used extensively for fishing and other recreational activities. Northwestern has determined that the lowest-cost way of meeting this demand will be from natural gas. From an environmental perspective, it is partly good news that Northwestern is choosing to expand natural gas rather than coal, which has traditionally been the cheapest energy source prior to the fracking boom (in fact the big story of American energy use over the last 10-15 years is the shift from coal to natural gas, perhaps the subject of a future post). But natural gas is still a major carbon emitter, and environmental advocates are angry that the plan will not expand renewable energy purchases. The plan also does not draw down on energy purchased from the Colstrip coal plant as some other utilities have done.

In short, Northwestern’s plan is to expand the use of fossil fuels at a time when the early impacts of climate change are becoming more immediate (eg the wildfires in California and Australia). The cost of renewables has fallen significantly in the last decade, but (at least according to Northwestern) they are not yet cost-competitive with coal and natural gas in a state with relatively low solar energy potential.

But the lower costs of fossil fuels are only the direct costs of production, and do not incorporate the “external” costs of pollution and climate change. These are sometimes called the “social cost of carbon” which is an actual number estimated by the US government and required to be considered in cost-benefit analysis for federal regulations. But in the absence of carbon pricing or much of any incentive from the state or federal government to invest in renewables, privately owned utilities have little incentive to consider external costs. Until the cost of renewables falls below the direct production cost of energy from fossil fuels, expanding renewable use will require political solutions.