Back in August 2016, I wrote a post that started off as, “Despite the one of the lowest wheat planted acreage in three decades in response to already record high inventories in the United States and the world, the 2016 production conditions have been arguably ‘too’ good.” In 2019/20, the story is similar.

In 2018 and early-2019, U.S. producers reacted to low global prices and continued high global inventories by reducing the planted acres of both winter and spring wheat. There were approximately 31.7 million planted acres of winter wheat in the U.S. (a 2.3% year-on-year reduction and the lowest in thirty years) and 12.4 million planted acres of spring wheat (a 5.8% year-on-year reduction and the fifth-lowest in the past thirty years). Overall, in 2016, national acreage decreased 10.2% year-over-year and in 2019, acreage decreased 3.5% year-over-year.

However, despite producers’ management responses to low prices in 2018/19, production conditions in the United States (coupled with the continued uncertainty about international trade) has resulted in further declines in prices.

For example, in both 2016 and 2019, wheat had unexpectedly high yields. Specifically, in 2016, the national average spring wheat yield was 47 bushels per acre and the winter wheat yield was a record 55 bushels per acre. In 2019, spring wheat yield is projected at 49 bushels acre (which could be the highest since the USDA began maintaining records in 1919) and winter wheat at 53 bushels per acre (which would be the second highest on record; only the 55 bushels per acre yield in 2016 would be higher).

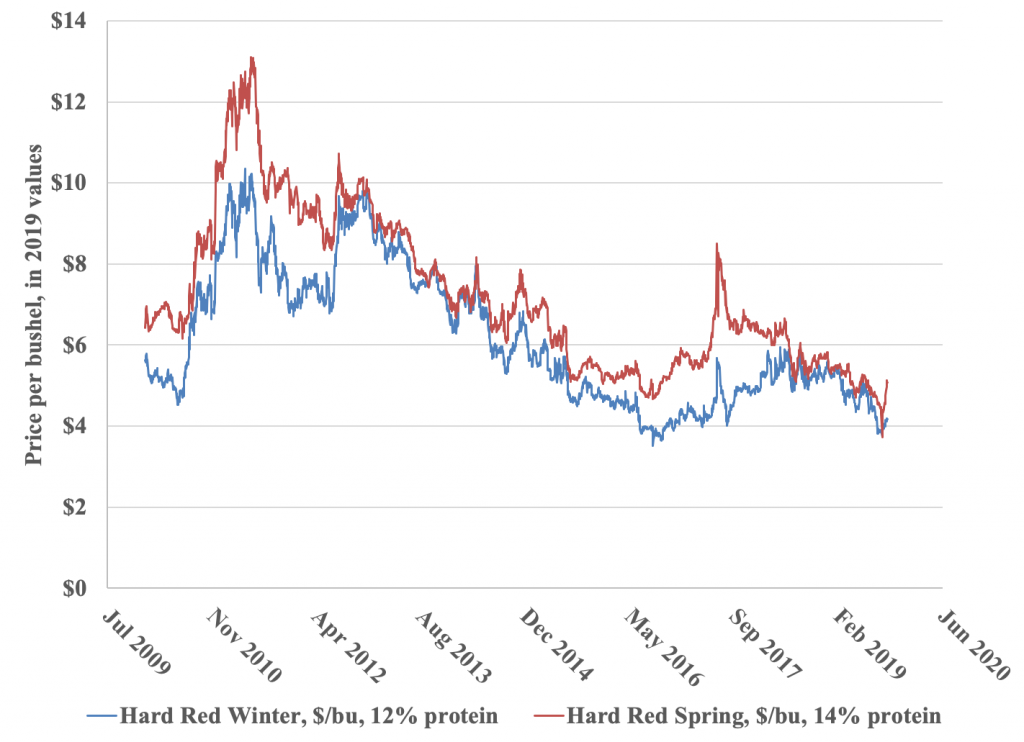

While this unexpected production increase is certainly not the only factor driving low market prices (trade uncertainty and global inventories are two examples of other major constraints), the fundamentals are likely important. What has been the impact on prices? The figure below shows that for winter wheat, 2019 harvest prices are only slightly higher than those in 2016. For spring wheat, the 2019 September prices are at the threshold of being the lowest in the past decade.

While the situation is certainly not great for wheat producers, there are two pieces of potentially uplifting news. First, the U.S. and Japan recently agreed to a long-awaited preferential trade agreement, which should increase the price competitiveness of U.S. wheat in one of its largest export markets. Second, similar to 2016, the beginning of the 2019/20 marketing year may be the floor to the wheat market, with prices potentially getting back to a historical average.

(Photo by Elias-Daniel is licensed under CC BY 4.0)