The 2018/19 marketing year has been a rough one for U.S. pulse crop producers. Relative to average prices observed over the past ten years, pea prices were down approximately 30%, lentil prices were down more than 50%, and chickpea prices declined by approximately 40%. In production regions such as Montana and western North Dakota—where wheat–fallow rotations have dominated for nearly a century until the rise of pulses over the past 20 years—it might be reasonable to conclude that when faced with challenging markets, farmers would quickly and substantially reverse away from pulse crops and place their land into either wheat or fallow. And if this is the case, then a market like 2018/19 (and the highly uncertain prospective 2019/20 pulse market) would be the lynchpin to this kind of reversal.

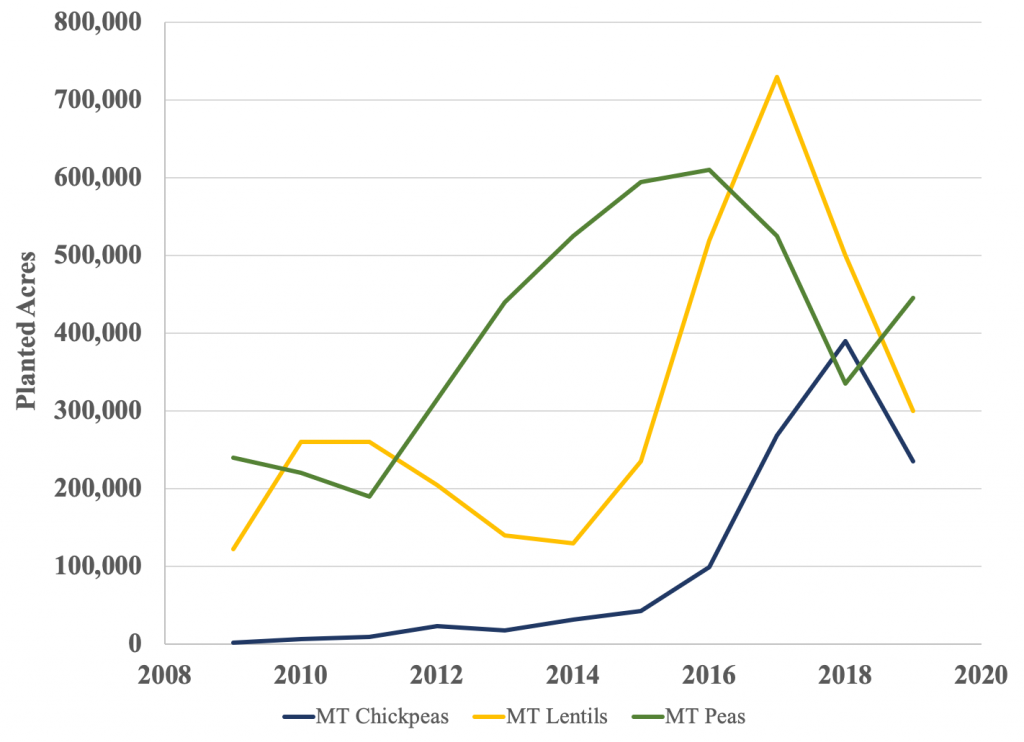

However, the most recent USDA Prospective Plantings report (March 29, 2019), which documents findings from a survey of farmers about their intentions to plant, shows that perhaps pulses may not be just a fad in Montana. The figure below shows that while lentil and chickpea acres are expected to decline, pea acreage is actually projected to increase relative to 2018. Specifically, pea acres are expected to increase by approximately 33%, while both lentil and chickpea acres would drop by about 40% each.

The apparently large reductions in chickpea and lentil acres should be placed in context with the fact that 2017 (for lentils) and 2018 (for chickpeas) were both years in which prices for the crops going into the production year were at relative highs (especially when considering these prices relative to other pulse crops that farmers could have planted). Therefore, some level of planted acres downward “rebound” was to be expected.

Despite the downward movement, the USDA still projects Montana total pulse plantings to be just under 1 million acres, which is the fourth highest on record. This seems to provide some evidence that while Montana (and likely western North Dakota) producers still respond to price expectations when making planting decisions, they view pulse crops as a more permanent part of their rotations rather than chasing any opportunity to find the crop with the highest price and quickly abandon that crop if markets retreat.

What about wheat?

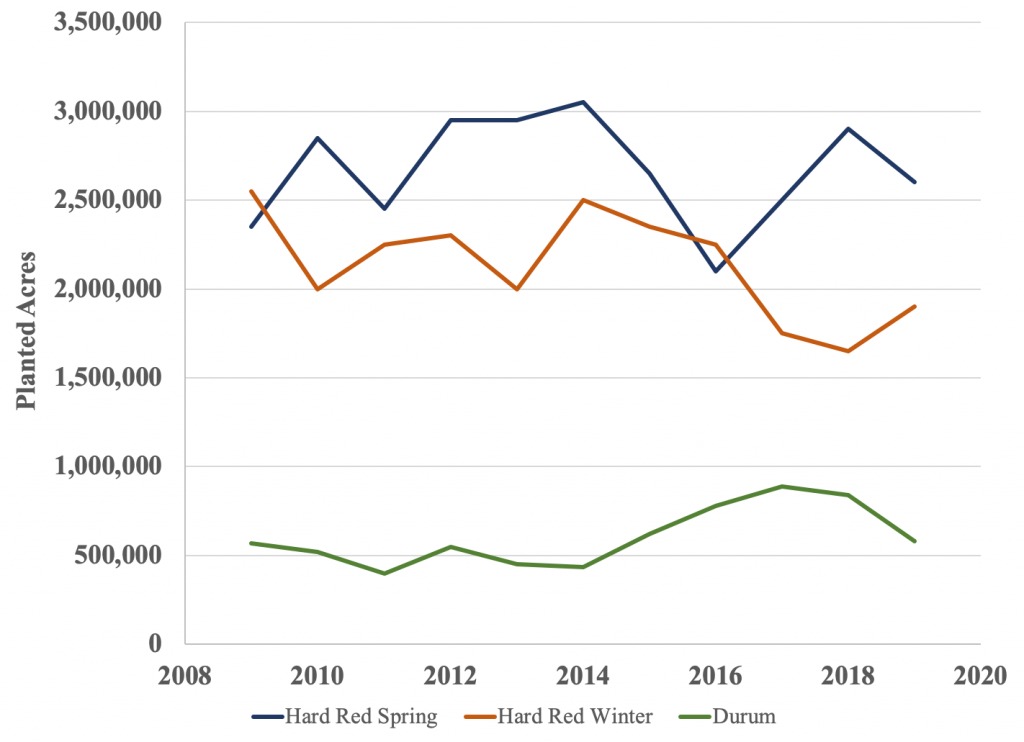

Wheat planting intentions are all changing toward their ten-year averages. After two years of increases in spring wheat plantings, the USDA is reporting a 10% decline in acres planted. Spring wheat prices have been relatively stable throughout the year, with a slight downward trend throughout the 2018/19 marketing season. Prices may have difficulties recovering as Canadian producers have indicated intentions to increase wheat planting, and there remains uncertainty about the effects of having Japanese consumers switch from U.S. wheat purchases to Canadian ones (as a result of Japan and Canada both being part of the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership). However, Montana’s 2019 spring wheat acres are expected to be in-line with the ten-year average.

Farmers have also indicated significant (approximately 31%) reduction in durum acres, likely largely as a response to stagnant low prices in the market. After three years of above-average plantings, durum acreage appears to be trending down toward the more typical 500,000 acres.

Unlike the spring crops, winter wheat appears to be making a rebound after multiple years of lower-than-average acreage. What’s perhaps somewhat worrisome is that winter wheat decisions were made in September/October 2018, when July 2019 futures prices were between $5.50 and $5.60 per bushel. Since then, prices have dropped by about $1.00 per bushel. If farmers were given a second opportunity to make planting decisions at today’s July 2019 futures prices, it’s not clear whether a similar 15% increase in planted acres would occur.

Which Crops Are Picking Up Acreage?

Overall, relative to 2018, wheat acreage is expected to drop by approximately 5.7% (about 310,000 acres) and pulse acreage by 20% (about 245,000 acres) in 2019. Where is this acreage going? The USDA report shows that some farmers are going to put their land into oilseeds such as canola and flax (projected to increase a total of 27,000 acres). Barley is also projected to increase by approximately 20,000 acres and there is a slight increase in the projected sugar beet acres. Other more minor and/or organic crops may also take up a few thousand acres.

However, these are not likely to make up for the total, approximately 550,000 acre reduction in planted wheat and pulse crops. Where is this land going? Some is likely to go into fallow, as most Montana producers are familiar with this management strategy. Perhaps other land will be enrolled (or re-enrolled) into the Conservation Reserve Program, for which the 2018 Farm Bill raised the total cap from 23 million to 27 million acres. Montana already has one of the largest area of land enrolled in the program. Perhaps other producers will use the land to plant cover crops or employ another agronomic management technique.

Where are you allocating your acres? Have you changed your management strategies in response to market prices? What factors have impacted your decisions?

2 Comments

I think we will see a revision in spring wheat on the June acreage report. Last year USDA increased spring wheat planted acres by 450K from March to June report. The final number should be at least in line with last year at around 2.9 million acres of spring wheat.

It’ll also be interesting to see how/whether things adjust in light of the continued wet weather we’re seeing, as a result of delays in seeding and (potentially as a result) substitution to later-planted crops.