In August, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) released their annual farmland value estimates for 2021. The NASS estimates are derived from a survey, administered each June, in which farm operators are asked to estimate the market value of their land. For states with property transaction price non-disclosure rules, such as Montana, the NASS estimates represent one of the only publicly available sources of farmland value estimates.

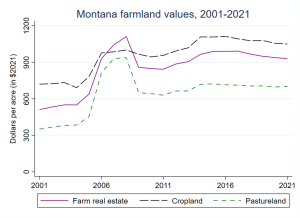

Per the latest survey, after adjusting for inflation using the Federal Reserve’s GDP implicit price deflator, the values of cropland ($1,050/acre) and total farm real estate ($930/acre; all farmland and farm-related buildings) exhibited year-on-year declines of 1%. The declines for cropland were similar in relative magnitude, at roughly 1%, for both nonirrigated ($835/acre) and irrigated ($3,050/acre) land. Pastureland value ($700/acre), in contrast, increased over the past year, albeit slightly (< 1%). In part, these changes reflect the high rate of inflation that has overtaken the US economy since 2020, which pushes up the real value of farmland from previous years. In fact, in nominal terms (i.e., without the inflation adjustment), cropland and farm real estate values actually increased by 2% over the past year, while pastureland value increased by 3%.

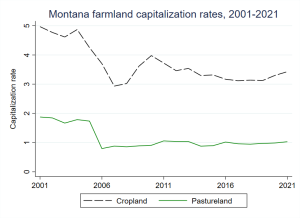

Cash rents showed inflation-adjusted gains between 2020 and 2021, increasing by 3% for cropland (to $36/acre) and 5% for pastureland ($7.20/acre). Renting land tends to be less common in Montana compared to other states, but cash rents are generally thought to be a reasonable proxy for net operating income. By taking the ratio of cash rent to land value, we arrive at the simplest version of the farmland capitalization rate (or “cap rate”), which measures the fraction of the land’s purchase price covered by annual proceeds from renting out the land. For example, a cap rate of 5, implies that the purchase price of the land will be fully paid for through rental income after about 20 years (since 100/5 = 20). As shown in the second figure, the combination of recent land value and cash rent changes has put upward pressure on the cap rate for both cropland and pastureland. At a current level of 3.43%, the cropland cap rate is at its highest level since 2013. The pastureland cap rate, at 1.03%, is also at its highest level since 2013.

In terms of where farmland values may be headed, one major thing to keep an eye on over the coming year is what happens to interest rates, which are inversely related to the value of long-held assets, such as land. The recent persistence of low interest rates is thought to have been a major driver of stubbornly high farmland values over the past several years. If economy-wide inflation continues to run high, the Federal Reserve may need to revise their target benchmark interest rate target upward, which would eventually put downward pressure on farmland values.

2 Comments

Dan,

I think the percentage increase is low. We have seen 10-25% increases in values across all land types, from Dec 2020 in Eastern MT.

Thanks, Monty. The thing to keep in mind with the USDA values is that they are based on surveys of producers asked for their own value self-assessments, rather than observed transaction/sale prices. Are the values you are referring to for eastern MT based on actual sales?