Key insights:

- Since 2000, pulse crops planted acres have increased by over 1,000% in the Montana/North Dakota region.

- In the initial expansion period, pulse crops were used to replace fallow in the traditional wheat–fallow cropping system. However, plant disease and policy-driven factors may lead to three- and four-year rotations, which can affect traditional land allocation outcomes.

- The wheat–pulse crop price ratio may be increasingly important to informing producers’ planting decisions.

- Future pulse crop production decisions will depend on international trade negotiations and the growth of the domestic pulse processing industry.

In the northern Great Plains region, the expansion of the pulse crops industry is not news. However, those outside this region may not be as familiar with this growth and the potential implications to the production and marketing landscapes of northern U.S. agriculture.

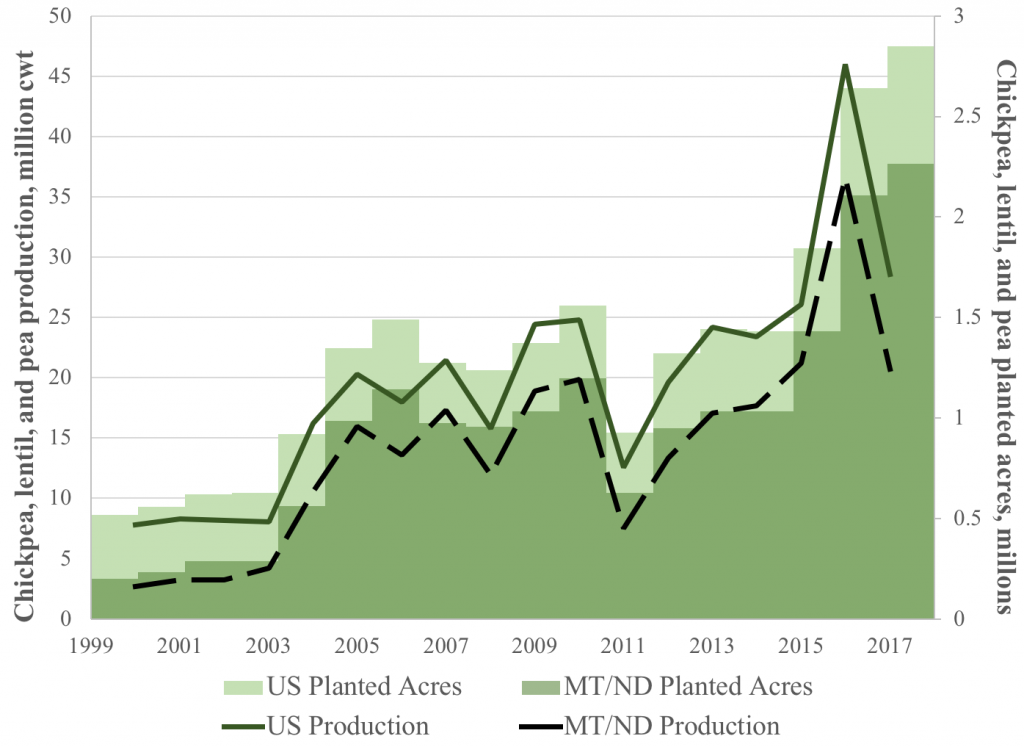

The growth of the pulse crop industry in the Montana/North Dakota region of the northern Great Plains has been rapid. The figure below shows that planted acres of pulse crops—primarily dry peas, lentils and chickpeas—has risen from approximately 200,000 acres to over 2.26 million between 2000 and 2017: a 1,024% increase. Accompanying growth in production of these crops has also occurred, with the Montana/North Dakota region representing the majority of the U.S. expansion.

Notes: Data are from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service.

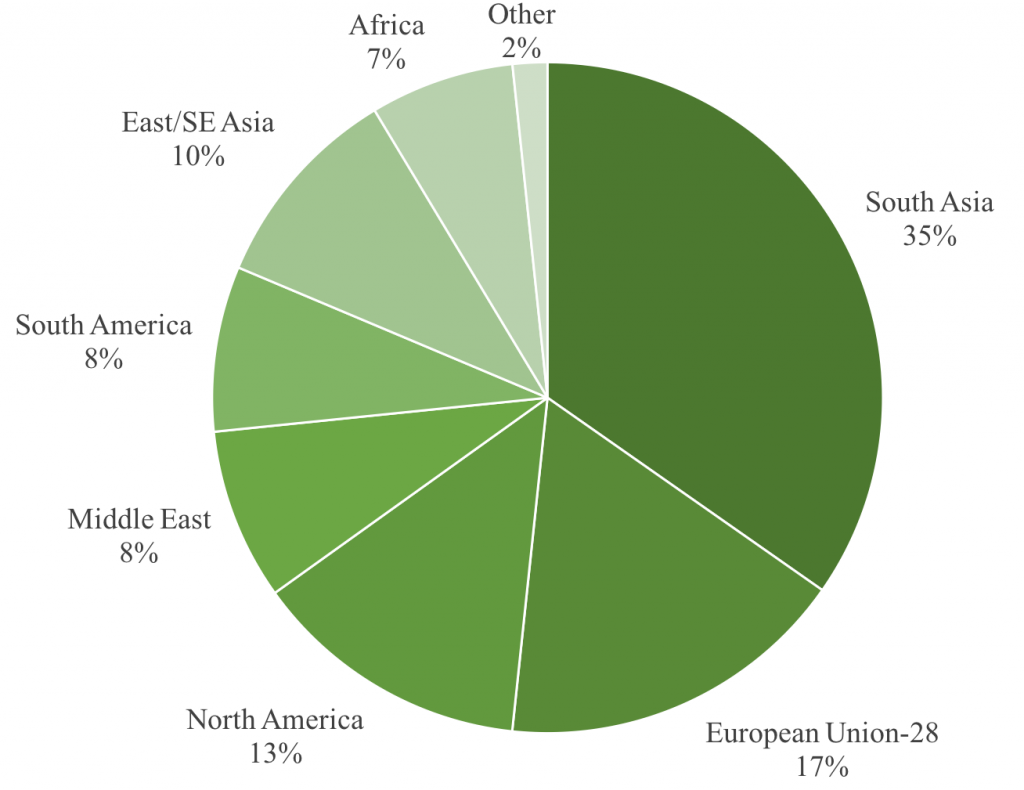

Over 80% of pulse crops produced in the United States are exported. Over the past decade, South Asia, on average, imported approximately 35% of the crops (of which nearly 90% has been procured by India), and Canada, Mexico, and the European Union representing an additional 30% of imports. The domestic industry remains relatively small, but also continues to grow as food manufacturers develop and market new products, including pet food with pulse-based protein, various snack foods, pea-based alternatives to dairy products, and even lentil beer, among many others.

Notes: Data are from the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service and represent the period between 2000 and 2017.

During the initial growth of the pulse industry, the impacts on farm business’ land allocation decisions was, arguably, minimal. Montana’s and North Dakota’s non-irrigated (dryland) wheat production region was characterized by a large number of wheat–fallow cropping systems, and through increased agronomic and soil science research as well as changes in government policies in the 2002 Farm Bill that essentially created a price floor, pulse crops became a viable product that could replace fallow by generating sufficient revenues for profitability.

More recently, however, increased and more intensive pulse cropping systems have led to significant disease pressures. For many diseases, the most effective solution is to increase timing between pulse crop plantings. At the same time, the USDA Risk Management Agency has begun to require that producers who wish to purchase crop insurance must maintain at least two years of non-pulse crop plantings. As a result, farm businesses have begun to expand their cropping systems and include alternative additional crops such as canola. Such expansion could affect the land allocation decisions that are observed year to year by substituting away from wheat and/or pulse acres.

Additionally, because of the pulse industry expansion, farm businesses are likely increasingly considering relative prices of wheat and pulse crops when making planting decisions. Similar to the classic corn–soybean price ratio consideration made by Midwestern farm businesses, the increased ability to, at the margin, consider the strength of wheat and pulse markets prior to deciding how to allocate farmland to a particular crop implies that land distribution and production outcomes could become more dependent on factors that influence both wheat and pulse crop prices. This increases the dynamics and complexity with which northern Great Plains crop markets operate.

What are the factors that might impact the relative wheat–pulse crop price ratio? Within the current marketplace, there are at least three that are immediately evident. First, Canadian production and inventories are especially important. As I’ve discussed in the past, while the U.S. pulse industry has certainly expanded in the past two decades, Canada has been one of the global leaders in the production and export of pulse crops, and has a substantial impact on the residual export demand faced by U.S. producers. Second is the uncertainty of trade disputes and resulting tariffs. Recently enacted Indian import tariffs, potential impacts of Chinese retaliatory tariffs, possible restrictions on the imports of higher-quality pulse crops into the European Union, and the renegotiations of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) are all critical in dictating export markets (and prices) of U.S. pulse crops. Third is the question of how quickly and how expansively will the domestic demand for pulse crop-products grow. Consumers in the United States represent a potentially large, high-income market, but the degree to which their desire to consume pulse products and the degree to which transportation and processing infrastructures can deliver those products are important questions that are yet to be answered.

Lastly, related but perhaps less obvious factors that could affect how the U.S. pulse industry evolves over the next decade include whether the export and/or domestic demand for pulse crops, the pace with which domestic processing can expand to satisfy the domestic demand, the demand and prices for other dryland crops, the willingness to produce pulse crops in other traditionally dryland wheat states (e.g., Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma), and whether domestic farm policies alter pulse crop demand and/or production incentives.

What are other factors that may be important? How has the growth and recent uncertainty in agricultural markets affected your land allocation decisions?

(Photo by Dani and Rob is licensed under CC BY 4.0)