The following is a summary of an undergraduate research project conducted by Jamie Douglas, an agricultural business student in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Economics.

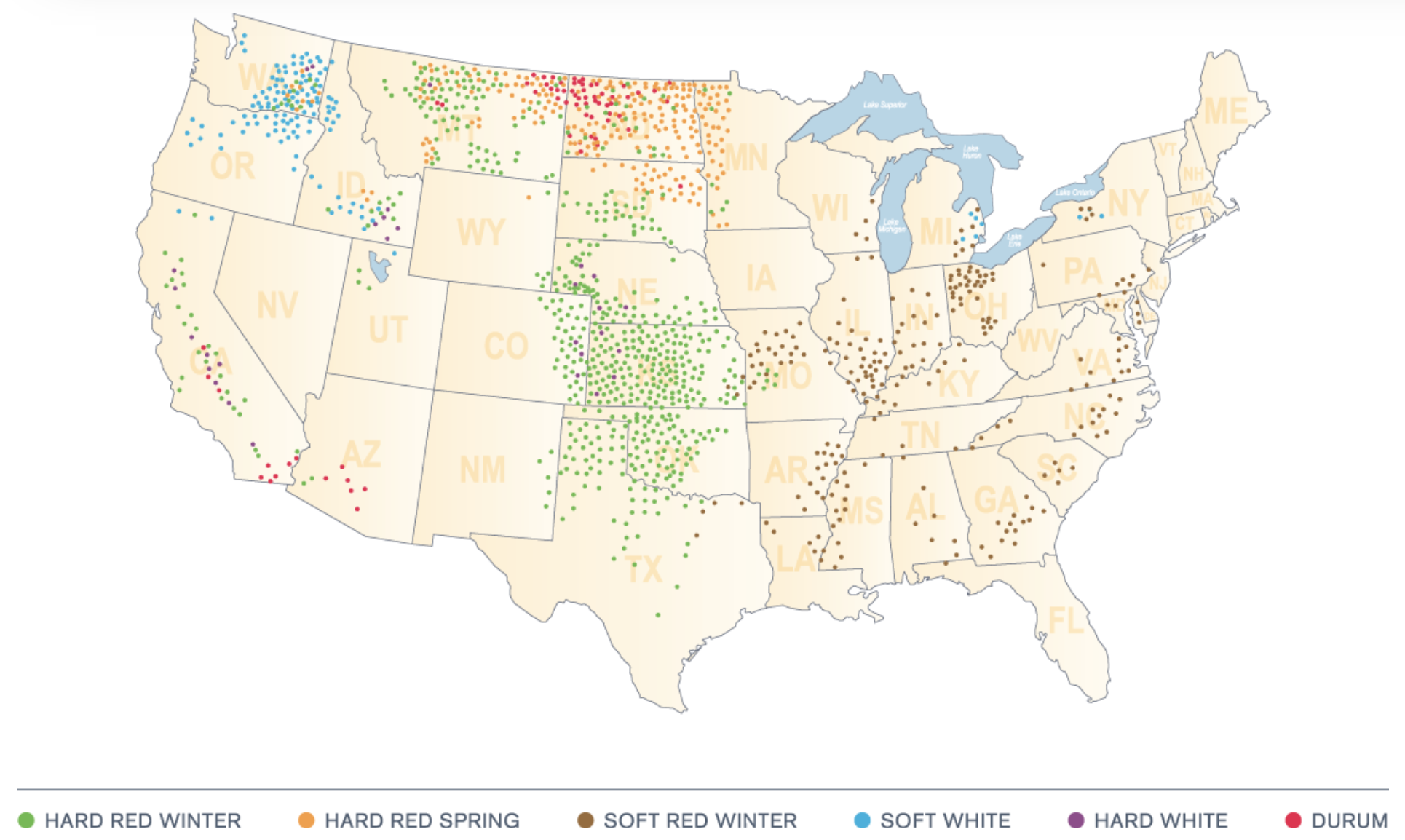

Soft white wheat is a class of wheat that generally has lower protein and higher carbohydrate levels. It is used primarily to make flour for the production of pastries, cookies, cakes, pancakes and waffles. In the United States, soft white wheat (SWW) is grown mostly in eastern Washington, northern Oregon, and parts of Idaho and northern California.

Source: US Wheat Associates

Despite SWW being produced in most of the Pacific Northwest, there are no market-based tools for managing price uncertainty. Unlike hard red winter wheat, hard red spring wheat, and soft red winter wheat, SWW does not have a futures contract product that could be used to discover and hedge price volatility.

As a result, a common price management strategy is to use the soft red winter (SRW) wheat futures contracts—traded on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange—as a proxy for SWW wheat. However, there are numerous reasons that this may not be an optimal approach. The two primary reasons are that soft red wheat is grown in the eastern part of the United States and much of that wheat is either processed in the midwest or east or exported from the Great Lakes or Gulf Coast regions. On the other hand, SWW is grown in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) and much of the wheat is exported from Oregon and Washington ports. As such, using the SRW contract to proxy for SWW prices may not be particularly accurate.

The goal of the undergraduate research project was a first attempt to develop a proxy “futures” price instrument that can be used to forecast Portland SWW prices. Ultimately, we wanted to develop a data-driven price prediction model to aid soft white producers in their marketing decisions.

We collected historical daily price data from 1989 to 2018 for Portland daily cash prices as well as daily nearby futures contract prices for hard red spring, winter, and soft red winter wheat. We assumed January as the month when producers will be making marketing decisions and developed SWW Portland price forecast models for February, March, and April. The base models included information about the year’s average September (harvest) price in Portland, the current January price, and the futures contract prices for the three available wheat classes: hard red winter, hard red spring, and soft red winter. Two additional models included only information about the soft wheat markets (white and red) and only futures price information.

To test the models’ forecasting accuracies, we created a “rolling” one-year-ahead out-of-sample predictions, which estimated economic models from 1989 to the year preceding the predictions and then used this model to predict the next year’s February, March, and April Portland SWW prices. For example, after estimating models using data between 1989 and 2010, the resulting estimates were used to predict February, March, and April prices in 2011.

The most successful model was one that included only soft wheat variables. This model had the lowest out-of-sample forecast error terms of all three (all regressors, soft wheats, and hard wheats). As expected, accuracy of predictions decreased as distance from January increased. The best out-of-sample predictions were for February Portland SWW prices, averaging around 40 cents per bushel of error. That is, in January, the model could predict February Portland SWW prices with a range of approximately 40 cents per bushel higher or lower than the actual observed price.

For March and April, prediction errors were typically between 37 and 63 cents per bushel. However, predictions for 2018 were particularly poor for the March and April models. We conjecture that this may be tied to the fact that during 2018, protein premiums for hard red spring were unusually high, which may have resulted in greater demand and port inventory capacity for hard red spring wheat. This could have reduced the handling capacity for soft white wheat, resulting in an underestimate of the predicted SWW prices for 2018.

The findings indicate that producers could consider looking at the September and January soft white wheat cash prices and the soft red winter wheat prices to inform them of prices and, potentially, marketing decisions for February–April. However, in years when protein premiums are particularly high, it is important to incorporate that information as well.

Jamie, who has transitioned into working on his family farm in eastern Washington after graduating in Spring 2020 from MSU, will employ this model to make marketing decisions on his own operation. He hopes to continually refine the model to make it more robust and helpful in analyzing a market without futures contracts.

What information do you use to inform marketing decisions and price knowledge when futures contracts are not available?

(Photo by Knowles Gallery is licensed under CC BY 4.0)