Access to a stable workforce and worker safety were primary concerns in agricultural production in 2020. The closure of multiple meat packing plants throughout the country demonstrated that vulnerability of workers in essential industries makes essential industries similarly vulnerable. Agricultural economists are still trying to gain better understanding of the vulnerabilities and potential flexibility of the U.S. food supply system given what we can observe from the shocks to the food supply system in 2020.

Limited labor migration, particularly across international borders, could have severely reduced farmers’ access to workers. Simultaneous closure of restaurants and cafeterias shocked agricultural output demand and by extension, farm labor demand. The net effects of these shocks on agricultural employment is theoretically ambiguous, but employment data are slowly becoming available through the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) administered by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

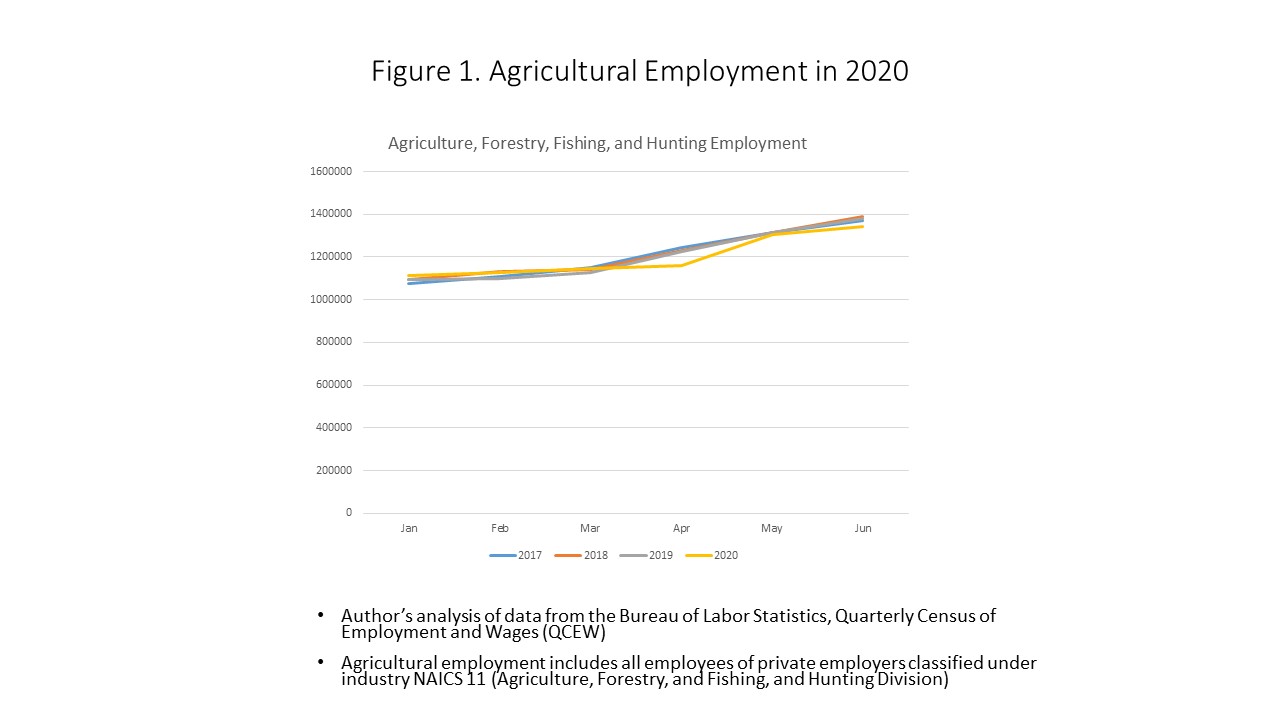

Preliminary analysis of the QCEW from January-June shows that there was a dip in agricultural employment in April compared to previous years (Figure 1). Employment rebounded to previous levels in May, but was lower in June compare to previous years.

There are important limitations of the QCEW. The QCEW includes all employees that an employer reports for Unemployment Insurance (UI). Some states do not count employees on small farms, and some states include H-2A agricultural guest workers in the UI while others do not.

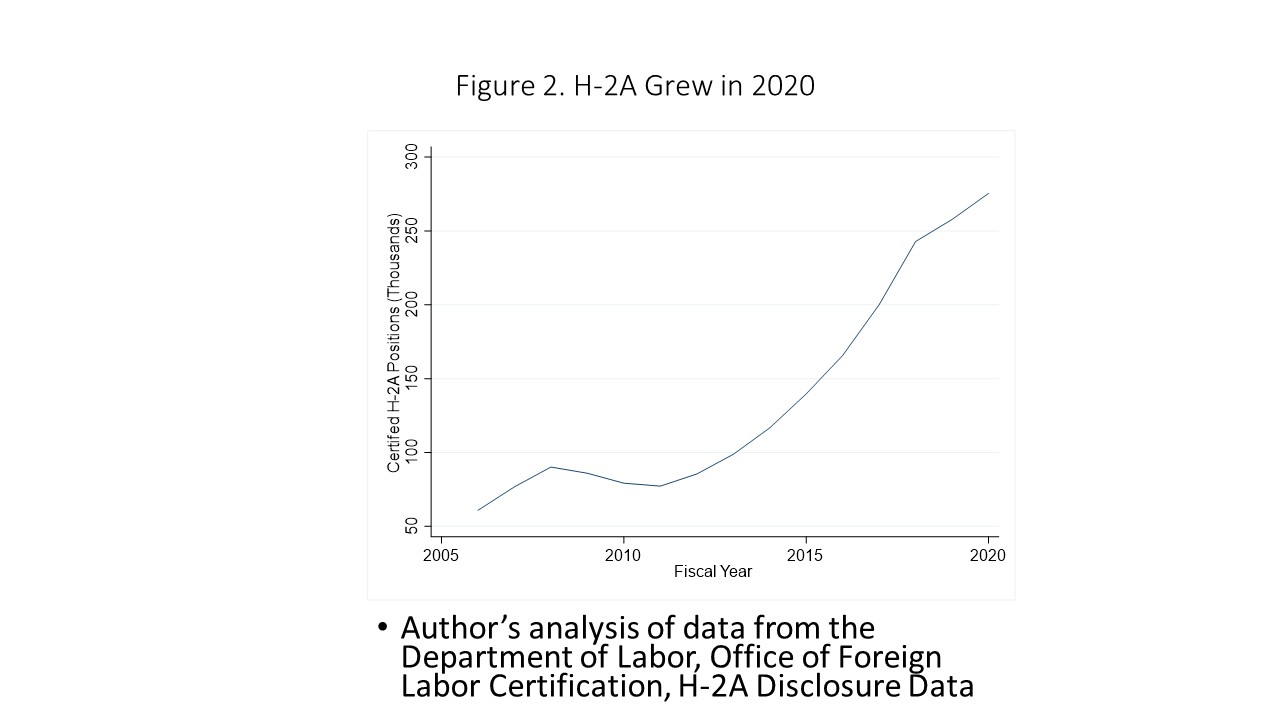

Similar to total agricultural employment, the effects of the pandemic on H-2A employment are theoretically ambiguous. On the one hand, in-person interviews at consular offices for H-2A visas were temporarily suspended. On the other hand, shocks to food demand could translate into negative shocks to H-2A demand, and high unemployment rates in the United States could reduce the need for guest workers. Nevertheless, H-2A employment grew in 2020 compared to 2019. Total H-2A certified positions grew by 17,647 workers in 2020 (see Figure 2). This was insufficient to fill the gap in total farm employment in the QCEW in June 2020 compared to 2019. The QCEW shows that there were 33,983 fewer crop and crop support employees in June 2020 compared to 2019.

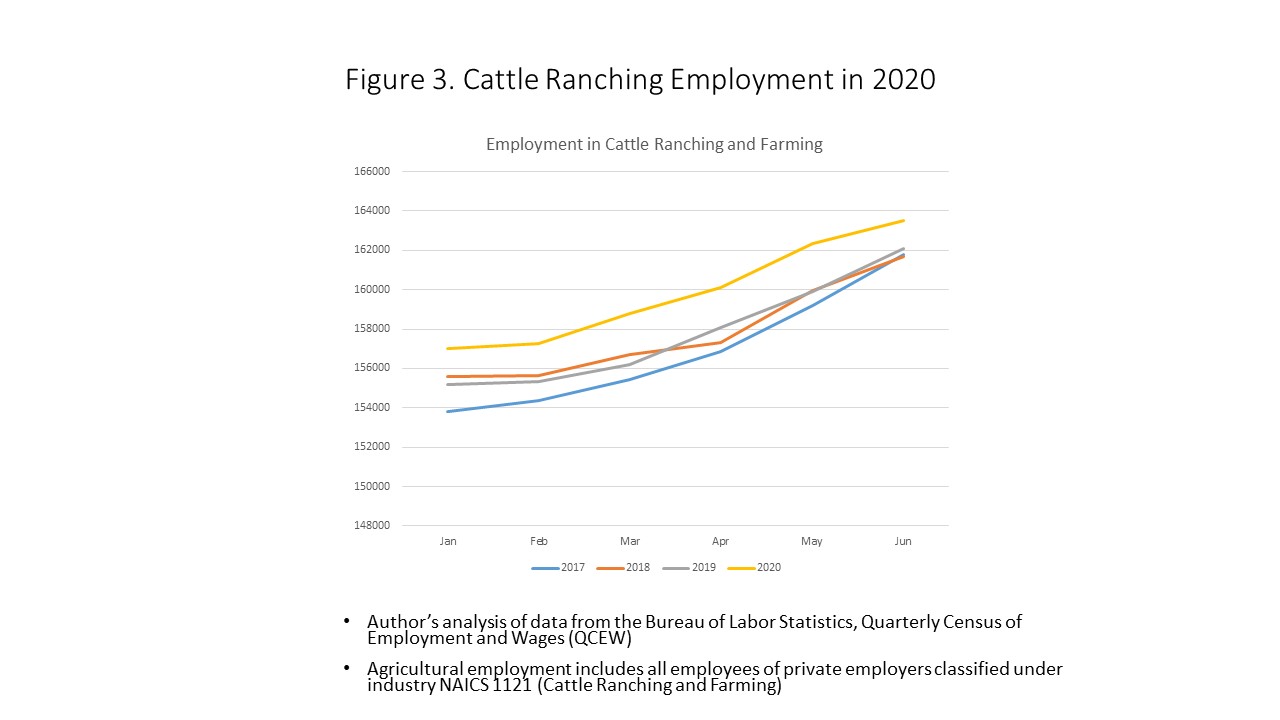

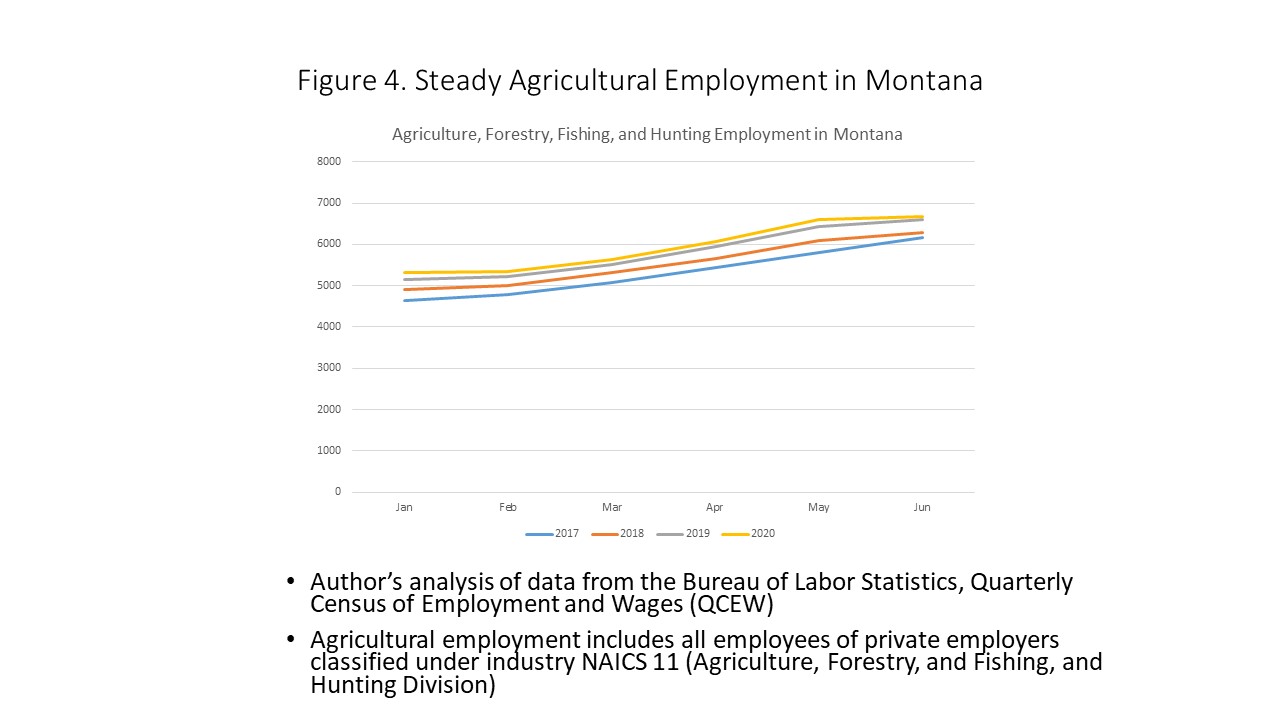

Thus, preliminary analysis of agricultural employment data shows a reduction in 2020 compared to previous years. Employment reductions were specifically in crop production and crop support. Employment in cattle ranching and farming, an important industry for Montana, was greater in 2020 compared to previous years (see Figure 3). In Montana specifically, agricultural employment (including crop employment) was similar in 2020 compared to 2019 (see Figure 4).