As smoke from wildfires fills the sky, most everyone is looking at the parched land around them with some trepidation. Drought is one of the most destructive natural disasters in severity, duration, spatial extent, loss of life, economic loss, social effect, and long-term impact (Sivakumar et al., 2011). Although rain eventually returns, drought can have long-term effects for agricultural producers, particularly in the cattle industry.

Many regions throughout the United States have experienced severe drought in recent years. Almost 12 percent of Montana is currently experiencing “exceptional” drought (Wilson, 2017). In 2011, over 70 percent of U.S. crop and livestock production was impacted by drought. In 2012, 67 percent of cattle production and 70-85 percent of corn and soybean production were impacted by drought (Countryman, Paarlberg, and Lee, 2016).

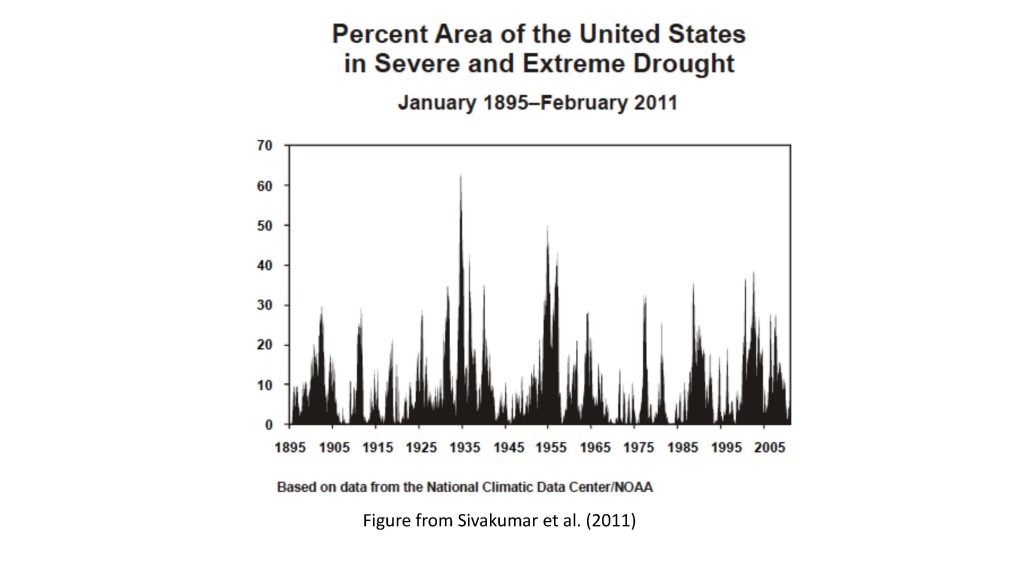

The figure below illustrates the spatial extent of droughts in the United States since 1895. The Dust Bowl of the 1930s stands out with the tallest spike, and severe drought events throughout this period appear to cluster. Droughts since the 1990s have been relatively long and severe. What does this imply for U.S. cattle producers?

The effects of drought can persist for several years in the cattle industry. As feed costs rise, cattle producers typically increase cattle slaughter. The rise in supply of cattle causes the price of live cattle to decrease in the short-run and beef cattle inventories to decrease in the long-run. Livestock industries usually take longer to recover than crop industries do because of the drought-induced decrease in breeding stock.

Countryman, Paarlberg, and Lee (2016) simulate the impacts of the 2011-2012 drought on the beef supply chain. They estimate that feed costs should return to their baseline prices a little more than 2 years after the drought. However, breeding inventories, the finished cattle slaughter, and finished cattle prices are expected to take closer to 8 years to return to baseline levels. Cattle slaughter initially rises at the onset of a drought, but then diminishes below baseline levels and remains low until producers build up the breeding stock again. Conversely, the price of cattle initially declines as the market is flooded with low-weight calves and culled cows. After slaughter declines, cattle prices rise above baseline and slowly work back down as breeding stock and slaughter rise again.

The 2014 Farm Bill contains two programs to reduce livestock producer risks associated with drought: the Livestock Indemnity Program compensates producers for the death of animals caused by adverse weather or predation by reintroduced species, and the Livestock Forage Disaster Program compensates producers for grazing losses due to drought or wildfire. These programs mitigate risk, but producers are not compensated for loss due to drought-induced culling, and producers located outside of a recognized drought region receive no compensation even though they are also affected by adverse shocks to markets and prices. Much is uncertain with respect to weather, droughts, and wildfire, but we can anticipate is that the livestock market will take a few years to recover from a drought.

Works Cited

Countryman, Amanda M., Philip L. Paarlberg, and John G. Lee. 2016. “Dynamic Effects of Drought on the U.S. Beef Supply Chain.” Agricultural and Resource Economics Review. 45(3): 459-484.

Sivakumar, Mannava V.K., Raymond P. Motha, Donald A. Wilhite, and John J. Qu (Eds.). 2011. Towards a Compendium on National Drought Policy. Proceedings of an Expert Meeting on the Preparation of a Compendium on National Drought Policy, July 14-15, 2011, Washington DC, USA: Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization. AGM-12; WAOB-2011. 135 pp.

Wilson, Sam. 2017. “12% of Montana is in exceptional drought—a once-in-century event, NOAA scientist says.” Billings Gazette. August 1, 2017.

1 Comment

Pingback: 17 years of drought monitoring – Fluidmotion