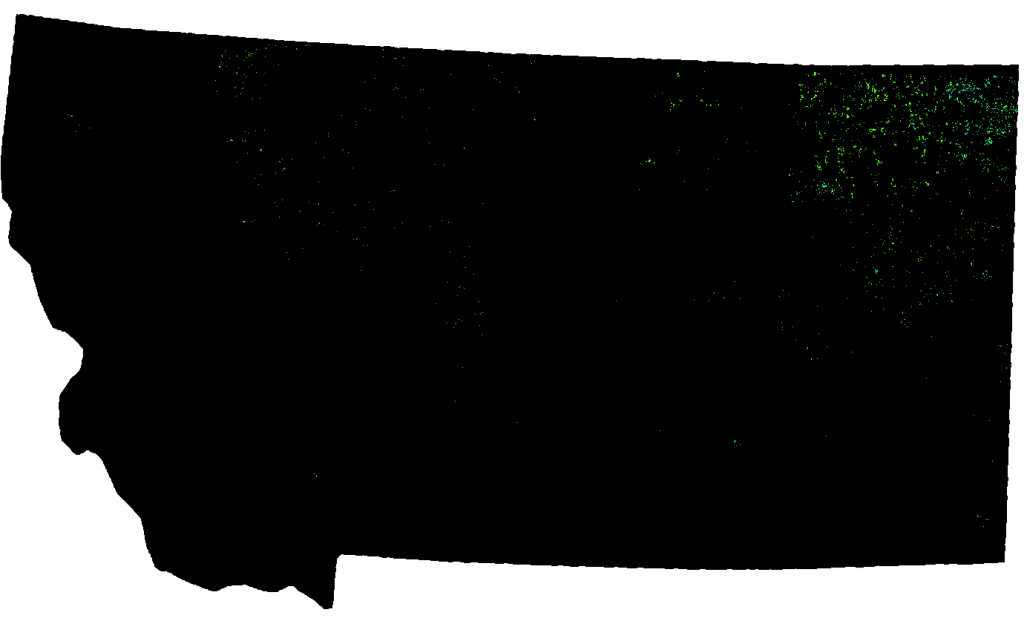

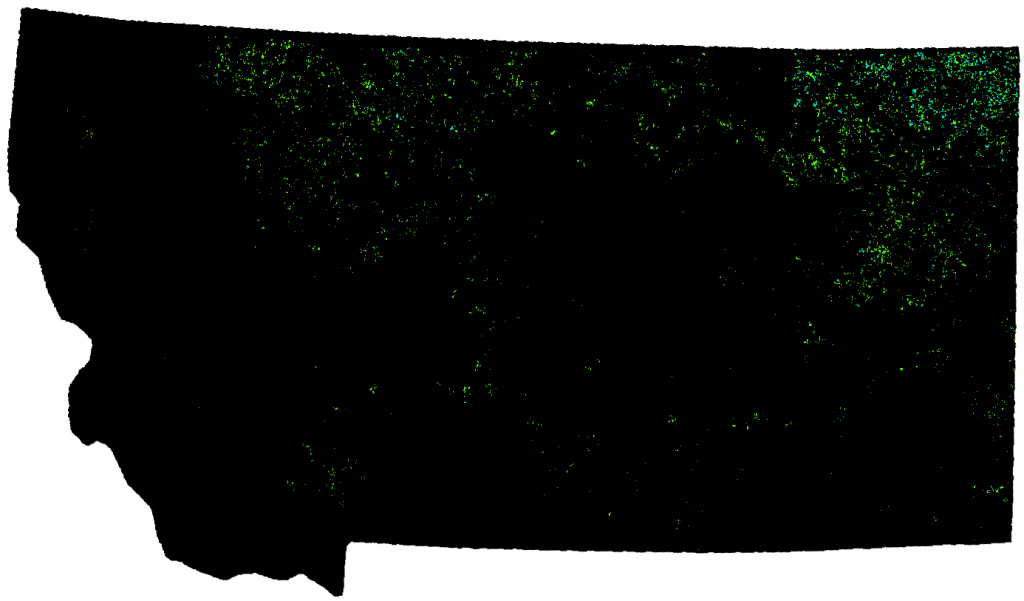

Pulse crop production—mainly peas and lentils—has expanded rapidly in the past decade in the northern United States. In 2016, just around 1 million acres were planted in Montana, and that number is expected to increase in 2017 (compare this to just over 200,000 acres in 2007). The figures below provide a visual representation of just how stark and rapid the expansion has been.

(a) Planted Pulse Acreage, 2007

(b) Planted Pulse Acreage, 2016

Figure: Planted Pulse Acreage in Montana, 2007 (top) and 2016 (bottom)

Source: USDA National Agricultural Statistical Service, CropScape (Cropland Data Layer)

This growth has been (appropriately) celebrated and has provided to many Montana and North Dakota producers a much-needed opportunity to diversify their production portfolios (and for many, making it a bit easier to face recent $4.00 per bushel wheat prices). But, with so much additional crop output being brought to market, little is known about the extent to which grain handling facilities have adapted and whether they are able to provide the needed supply chain capacity to operate effectively as pulse production continues to increase.

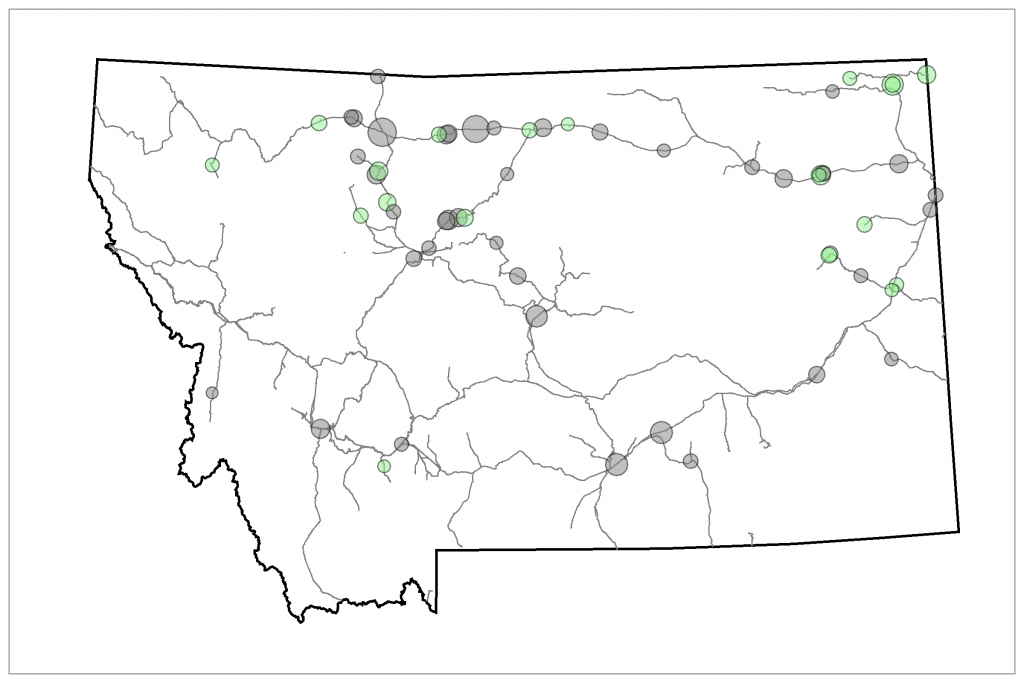

Using data provided by the Montana Wheat and Barley Committee, I mapped and calculated several descriptive statistics about the current state of Montana’s pulse handling industry. The map below shows active grain handling facilities in Montana (indicated by a circle), with green circles indicating those that accept pulse crops and gray circles showing those that primarily specialize in handling only small grains. The size of the circle indicates the relative overall storage capacity at the location, and the lines represent railways.

Figure: Locations of Active Grain Handling Facilities in Montana

The maps makes evident that despite the growth in Montana’s pulse production, there are still many more elevators that do not accept pulse crops, even in the northeast part of the state (the primary production area). In fact, only 34% of elevators in Montana handle pulse crops. Moreover, an average elevator that accepts pulse crops has an average capacity of 563,909 bushels, while an average elevator that specializes in wheat handling has a capacity of 773,307. On aggregate, out of the total available capacity at active Montana elevators, 29% of that capacity represents elevators that accept pulse crops while 71% of capacity specializes in wheat.

These statistics suggest that despite the rapid development of the northern U.S. pulse markets and increased focus on developing improved pulse crop varieties that can maximize farm productivity, there are still significant “growing pains” and questions that the industry must answer in order to realize its full potential, including:

- How to best handle significantly higher volumes of products?

- How to increase the quantity of labor for handling services, which are located in rural areas where the labor supply has become increasingly constrained?

- How much storage capacity to add at handling facilities, in case farmers may not have sufficient on-farm storage or may choose not store pulse crops?

- How to efficiently respond to increased demand for quickly moving pulse crops, which can oxidize and lose favorable aesthetic characteristics that are demanded in retail consumer markets?

- How to improve shipping logistics to deliver pulse crops to destinations that have not been traditional terminals for the northern U.S. markets (such as shipping pulses south to processing facilities in the Midwest and as exports to South America)?

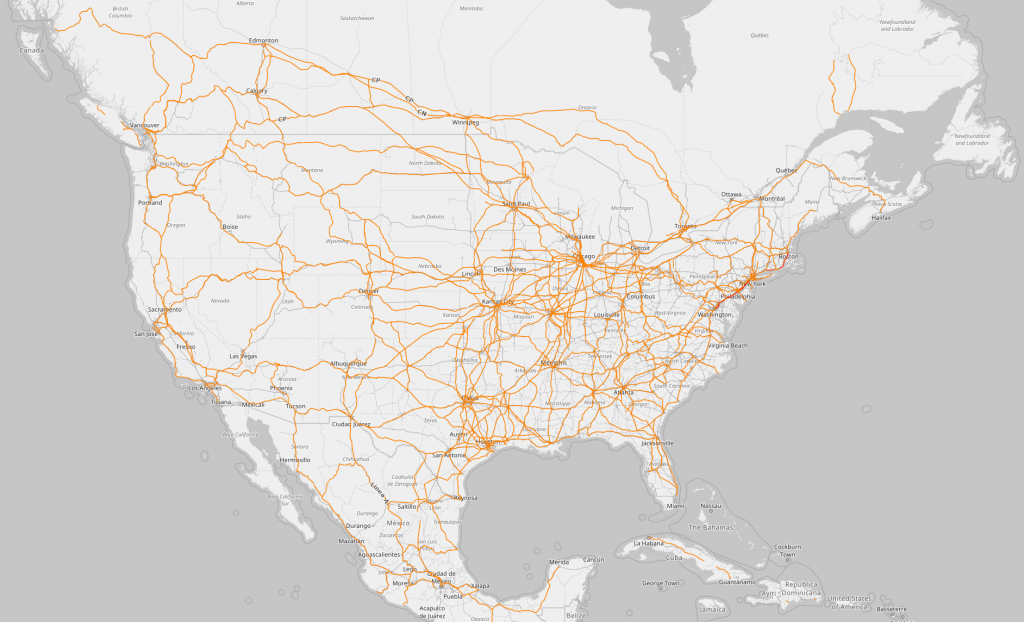

The map of the U.S. rail infrastructure (see below) illustrates the extent of the challenge described in the last bullet point. Northern U.S. wheat has traditionally been shipped either west to export facilities in the Pacific Northwest or east to the Great Lakes region. As such, rail lines through much of Montana and western North Dakota—the primary pulse production regions—have no north–south routes, and the only major north–south throughway does not occur until Minnesota. Therefore, shipping pulse crops to domestic destinations in the Midwest and to southern export terminals requires significant additional shipping costs on the part of the grain handler, which are likely to be passed down to grain elevators and to farmers in the form of lower price bids.

Figure: U.S. Rail Infrastructure

Source: OpenRailWayMap.org

Undoubtedly, the development and growth in northern U.S. pulse production is a boon to Montana and North Dakota producers. However, challenges within the supply chain beyond the farm level are critical to understand when considering the future evolution of this market.