(Photo by The U.S. National Archives is licensed under CC BY 4.0)

With the United States withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement, the US coal industry continues to hold the spotlight in the national news. In one recent story, Colstrip, Montana stood in as a case study of the many forces affecting towns and regions reliant on the economic activity generated by coal mining and coal-fired electricity generation. With the long-run decrease in total US coal production, documented last month in a post by AgEconMT’s Brock Smith, many are justifiably concerned about coal’s decline and demanding policies to mitigate or reverse its effects.

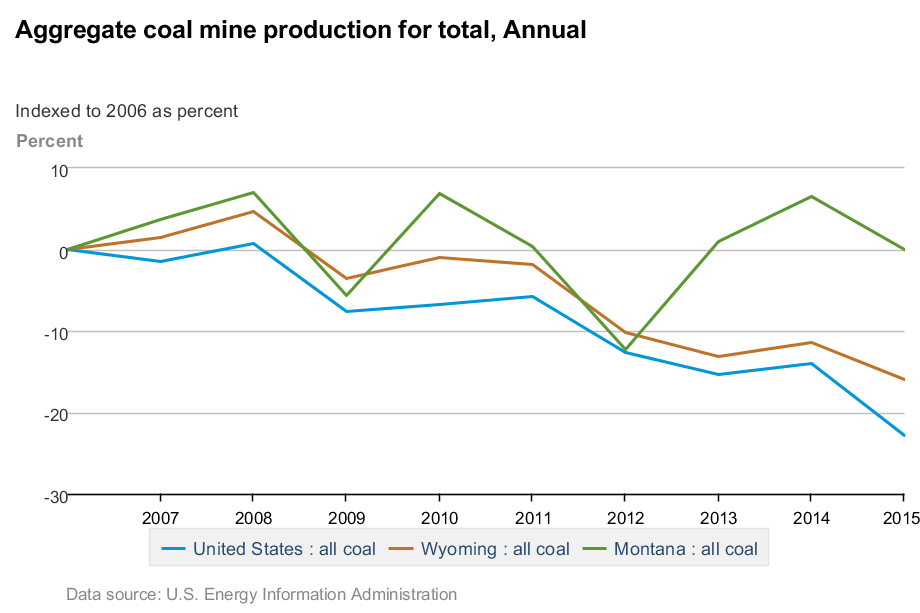

Coal production and coal-fired electricity generation are important to Montana’s economy, particularly the eastern half of the state. In 2015, Montana held 25% of the nation’s coal reserves and was the sixth largest coal producing state. More than seventy-five percent of the state’s coal production is exported to the Midwest or foreign markets, with the remaining coal used to power in-state electricity generation. As yet, Montana coal production has not exhibited the production declines as in other parts of the US. As the figure below shows, Montana coal production in 2015 was roughly equal to production in 2006, while Wyoming production had fallen about 15% and total US production fell nearly 23%.

More concern in Montana exists with respect to coal-fired electricity generation. Following the shut down of the J.E. Corette power plant in Billings in 2015, the conversation has centered on Colstrip and the decision by utility companies to shutter two of the four electricity generating units there. A number of bills in the recent Montana legislative session sought to address the uncertain future of coal-fired power generation in the state. Two bills (SB 338 and SB 339) sought to manage the shut down of generating capacity at Colstrip, the first by providing additional benefits for affected workers and communities and the second establishing plans for environmental remediation.

A third bill, House Bill 585 now signed into law, will loan the plant’s operator ten million dollars annually to keep the plant operating for the next five years. When government proposes such a policy to directly encourage coal production and use, one immediate question is whether the policy will actually change behavior. Will the additional money loaned to the plant’s operator actually induce them to produce and use coal and generate additional economic activity or are tax dollars being paid out for activity that would have occurred anyways? A recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper by economists Jonathan Eyer and Matthew Kahn provides some evidence on the question, drawn from the many incentives provided by state and local governments to encourage local coal production and the use of local coal for electricity generation. For example, Maryland has a $3 per ton tax credit for utilities buying in-state coal, and Oklahoma went as far as to pass laws aimed at preventing in-state power plants from buying out-of-state coal.

Eyer and Kahn find that power plants in counties or states with active coal mines are more likely to be coal-fired and are more likely to buy coal from within the same political jurisdiction. This result is robust to controlling for the distance between plants and mines. The fact that in-state mines have lower transport costs to in-state plants cannot explain the degree to which those power plants source in-state coal. Eyer and Kahn attribute this to a political mechanism: elected officials in areas where there is a high prevalence of coal mining have the incentive to enact policies that encourage power plants to buy local coal, both to maintain the wellbeing of their constituents and also stay in office.

This result suggests that policies like those enacted in Montana to encourage coal-fired power generation achieve at least some of their goals: more in-state coal gets used for in-state power generation than would otherwise. The open question is whether the benefits of this additional coal use to the state’s economy exceed the costs to taxpayers, both in terms of government spending and environmental and other costs borne by Montanans.

Note: Thanks to MSU Applied Economics graduate student Thomas Gumbley for his research assistance with this post.

(Photo by The U.S. National Archives is licensed under CC BY 4.0)