In March President Trump signed a sweeping executive order undoing many Obama-era environmental policies, most notably the Clean Power Plan, ostensibly in an effort to revive the floundering coal sector. This will be an interesting experiment in determining whether coal’s decline has been a result of onerous regulations or wider market forces. This question has particular resonance for Montana, which as of 2014 was the sixth largest coal producer in the country, and higher still on a per capita basis.

The general response from economists and commentators as to whether the order will bring back a flood of coal mining jobs was, to put it mildly, incredulous. “Trump can’t save coal” has been a typical refrain.

But hold off on the funeral arrangements. There is more nuance to the question of whether coal is dead than much of the commentary lets on. First, it is important to distinguish between coal output and employment. With only around 77,000 coal-mining jobs in the country, employment is indeed near rock bottom, but it has been lingering there for a long time. The primary culprit isn’t low demand or regulations, but automation. Huge mechanical shovels and other machines have largely replaced miners, as is seen by comparing employment and productivity over time:

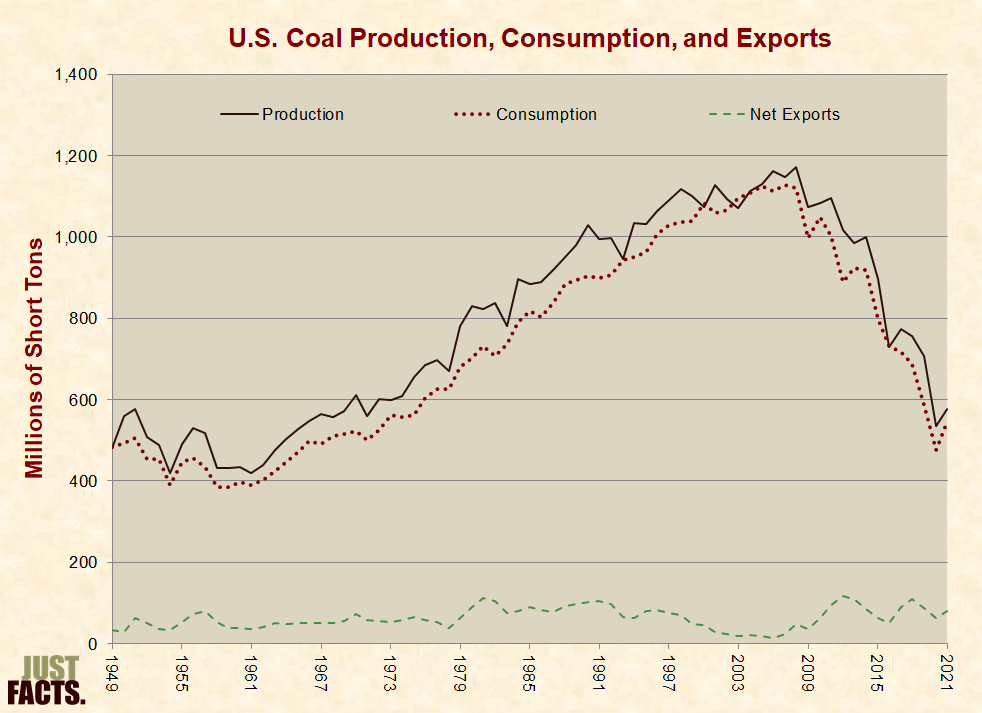

If we instead focus on overall production, things aren’t quite as bleak:

In 2015 output is still high by historic standards. However, it has dropped significantly from its 2008 peak. There are regional differences too: Appalachian production has been in steep decline since the turn of the century, while Wyoming has gradually become the country’s primary coal powerhouse, producing about four times as much coal as the next highest state as of 2015 (link). But overall, the industry has become considerably less profitable, as 44% of production comes from companies that have declared bankruptcy.

What is responsible for these troubles? The Clean Power Plan and other Obama-era regulations did raise the cost of coal production and use. However, market forces are likely more responsible. Most importantly, the fracking revolution collapsed the price of coal’s main competitor, natural gas, which just last year surpassed coal in share of American electricity generation:

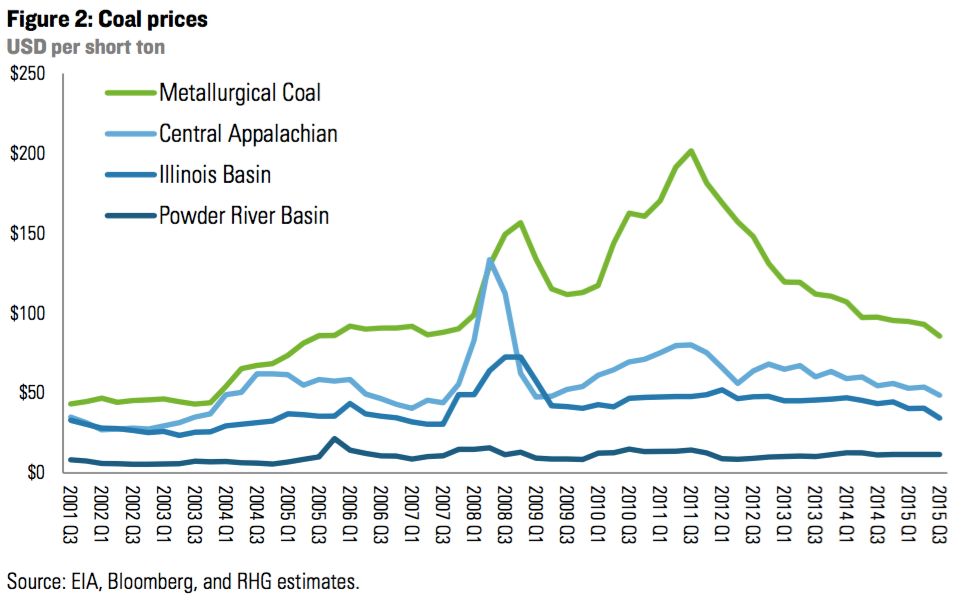

The pressure from natural gas may subside somewhat, as production has recently leveled off. However, another under-appreciated reason for coal’s troubles is shrinking demand from China for a special class of coal called “metallurgical coal” (or “met coal” for short), which has higher carbon content and is primarily used to make steel. As detailed here, exports of met coal to Chinese steelmakers was a major source of profit for US coal companies, but as the Chinese economy, and thus its steel industry, have slowed, the price of met coal has decreased, with severe impacts on US coal revenues:

With China’s construction boom continuing to slow and its economy apparently settled into a more modest growth trajectory, the demand for met coal does not appear likely to see a rebound.

To summarize, at the moment US coal production remains relatively high and is still a significant share of US energy production, but market forces are likely to continue the sharp decline seen in the last several years. President Trump’s executive order may slow that decline somewhat but will likely not reverse it. As for employment, mining jobs have gone for decades and are not coming back.