On Sunday night, I appeared as a panelist on Montana Ag Live. For those not familiar, MAL is a Sunday night call-in TV show produced by Montana PBS at their studios on the Montana State University campus featuring MSU College of Agriculture faculty as panelists.

On the show, I received an interesting question from a caller in Havre, asking if US farmers can deliver grain to Canadian elevators. I want to expand on my answer, since this issue of cross-border trade (farmers from one country selling to elevators in the other) is a part of the ongoing NAFTA re-negotiations. Northern Great Plains farmers have been quoted saying that it is much harder to deliver grain into Canada than vice versa. Some seek to similarly restrict Canadian wheat exports to the US. In April, US Senator Jon Tester of Montana passed a Senate resolution seeking the “fair and equitable” treatment of US wheat exports to Canada.

How much wheat moves across the US-Canada border?

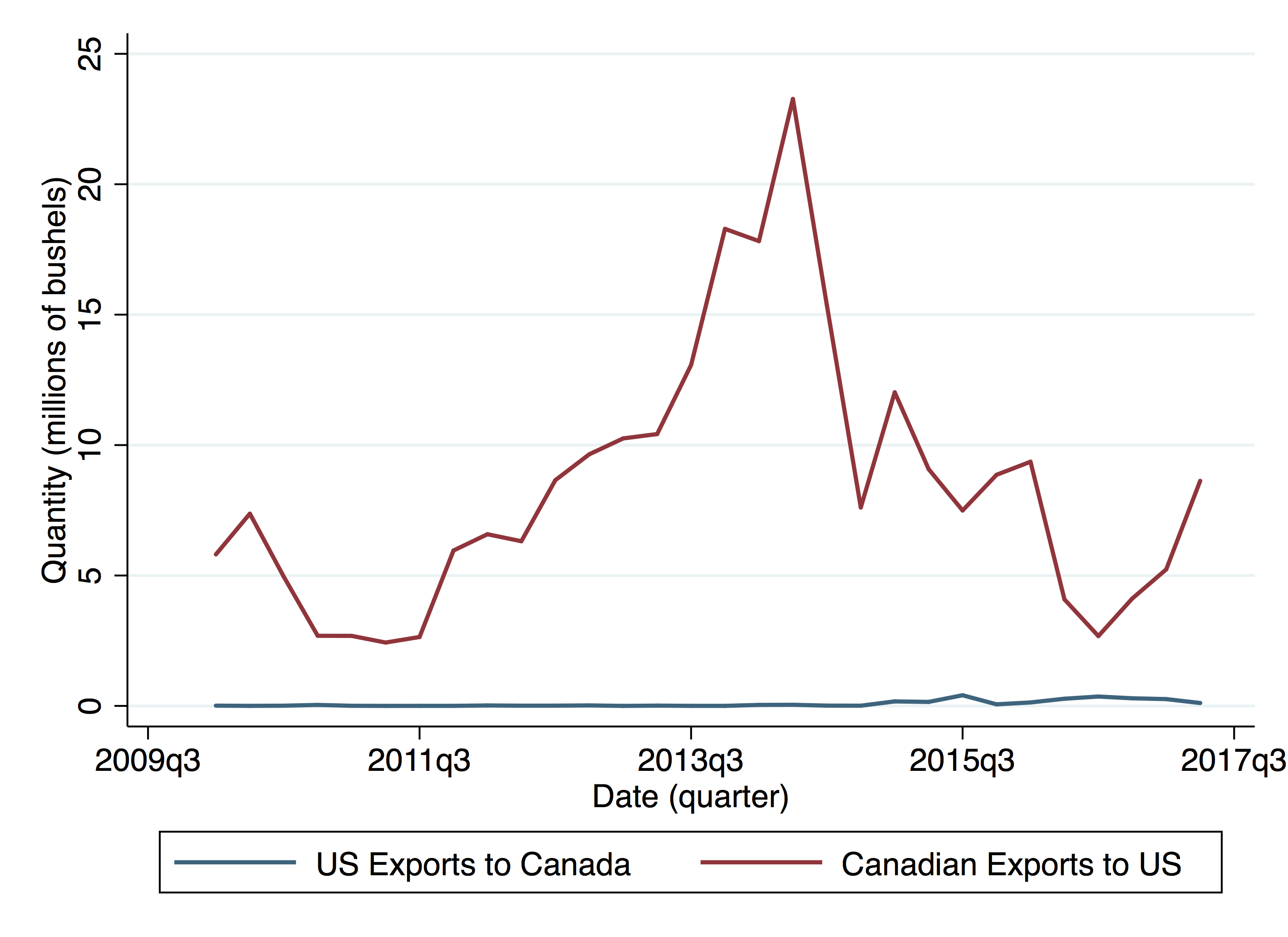

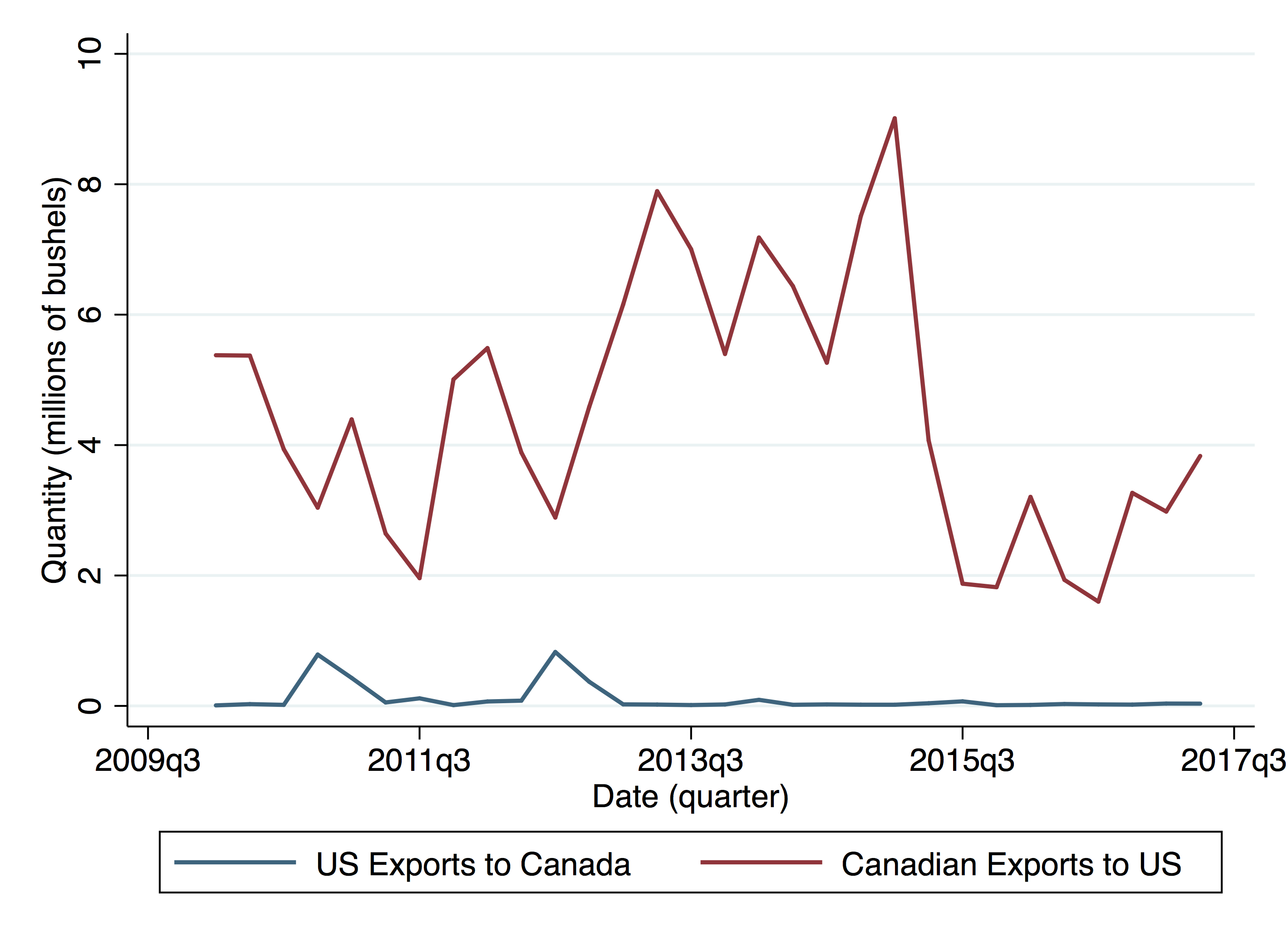

First, it is useful to understand how much wheat moves across the US-Canada border, particularly across the land border on the Northern Great Plains. The two graphs below show wheat exports to and imports from Canada in the two customs districts (Great Falls, MT and Pembina, ND) along this portion of the border. I’ve separated non-durum (mostly hard red spring) and durum wheat and excluded wheat used for seed. These quantities, collected by the US International Trade Commission, include wheat, moved by truck or rail, by farmers or elevator companies.

The graphs show that there is significantly more Canadian wheat crossing the border than US wheat. In a given quarter, the US imports approximately 6 million bushels of Canadian wheat and 4.5 million bushels of Canadian durum across the Northern Great Plains border. US exports to Canada are significantly smaller, on the order of a few hundred thousand bushels per quarter. The exception to these average flows was the 2013-2014 crop year when US imported around 20 million bushels per quarter from Canada. That year, Canada had a large crop and significant congestion in their grain transportation system.

Trade flows from Canada are relatively small in the context of overall US wheat production and exports, but similar in magnitude when we consider durum specifically. The US produces approximately 400 million bushels of hard red spring wheat and 75 million bushels of durum annually, with roughly 40% of US production exported each year. For spring wheat, annual imports from Canada are about 10% of worldwide exports. For durum, annual imports from Canada are about half of US worldwide exports.

What restrictions exist on grain delivered into Canada?

Wheat grading and variety registration regulations may account for some of the disparity in trade flows across the Canada-US border on the northern Great Plains. Both countries segregate wheat by class. In the US, there are six classes, including hard red spring and durum. Any wheat delivered to US elevators can be accepted into these classes, graded according to US quality standards, and receive the price offered for that grade.

Canada more closely links wheat grading and wheat variety registration. Only approved varieties can receive a grade in the nine classes specified by the Canadian Grain Commission. In the Canadian system, some classes are further segregated in order to maintain quality standards for that class. For example, only certain varieties may be delivered into the Canadian Western Red Spring (CWRS) class regarded as the highest class of milling spring wheat. While some US varieties are on this list, many are not. US spring wheat varieties commonly grown in Montana such as Vida and Reeder are not eligible for delivery as CWRS or other high value classes.

Would US growers benefit from harmonized wheat grading standards?

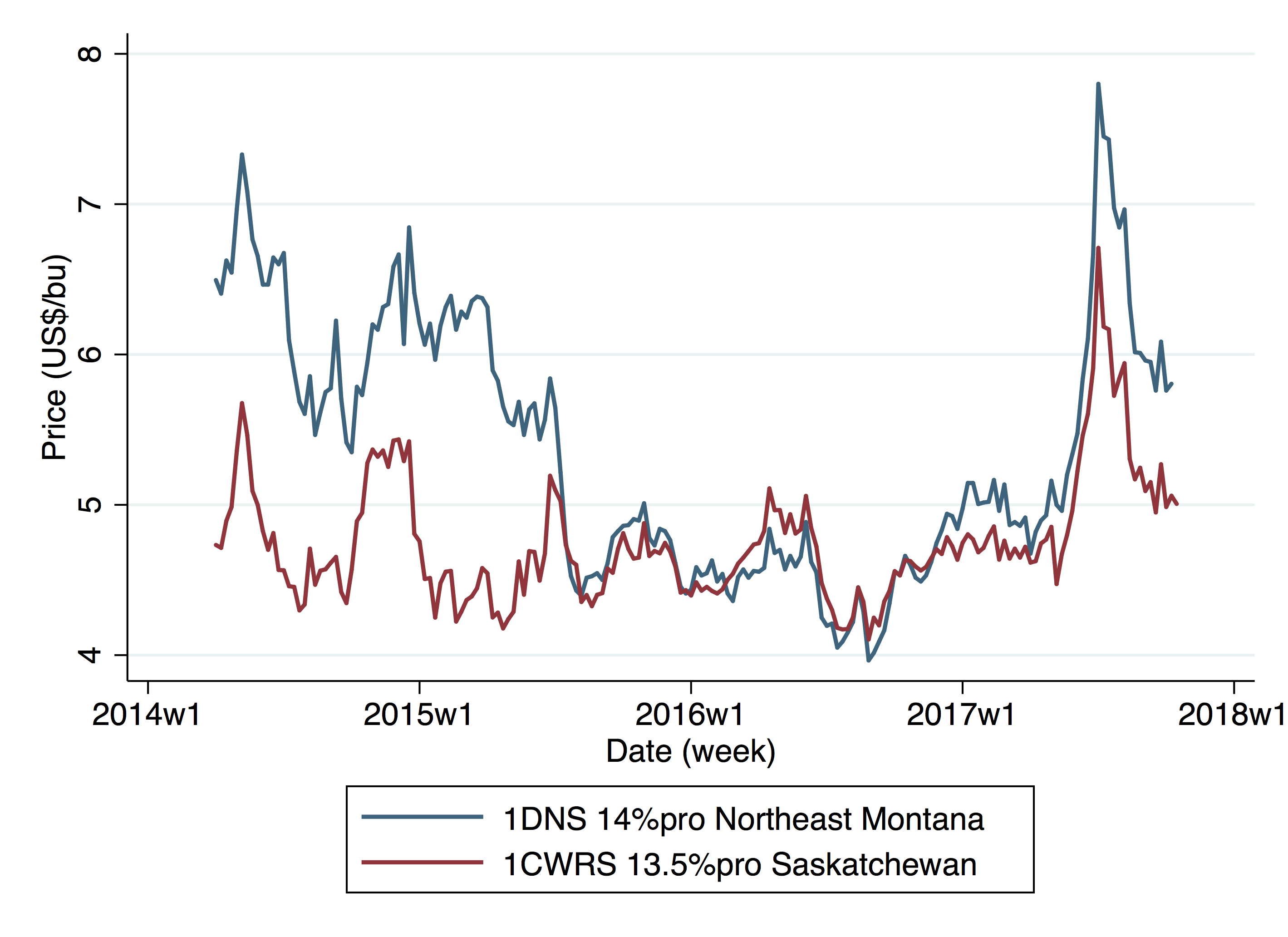

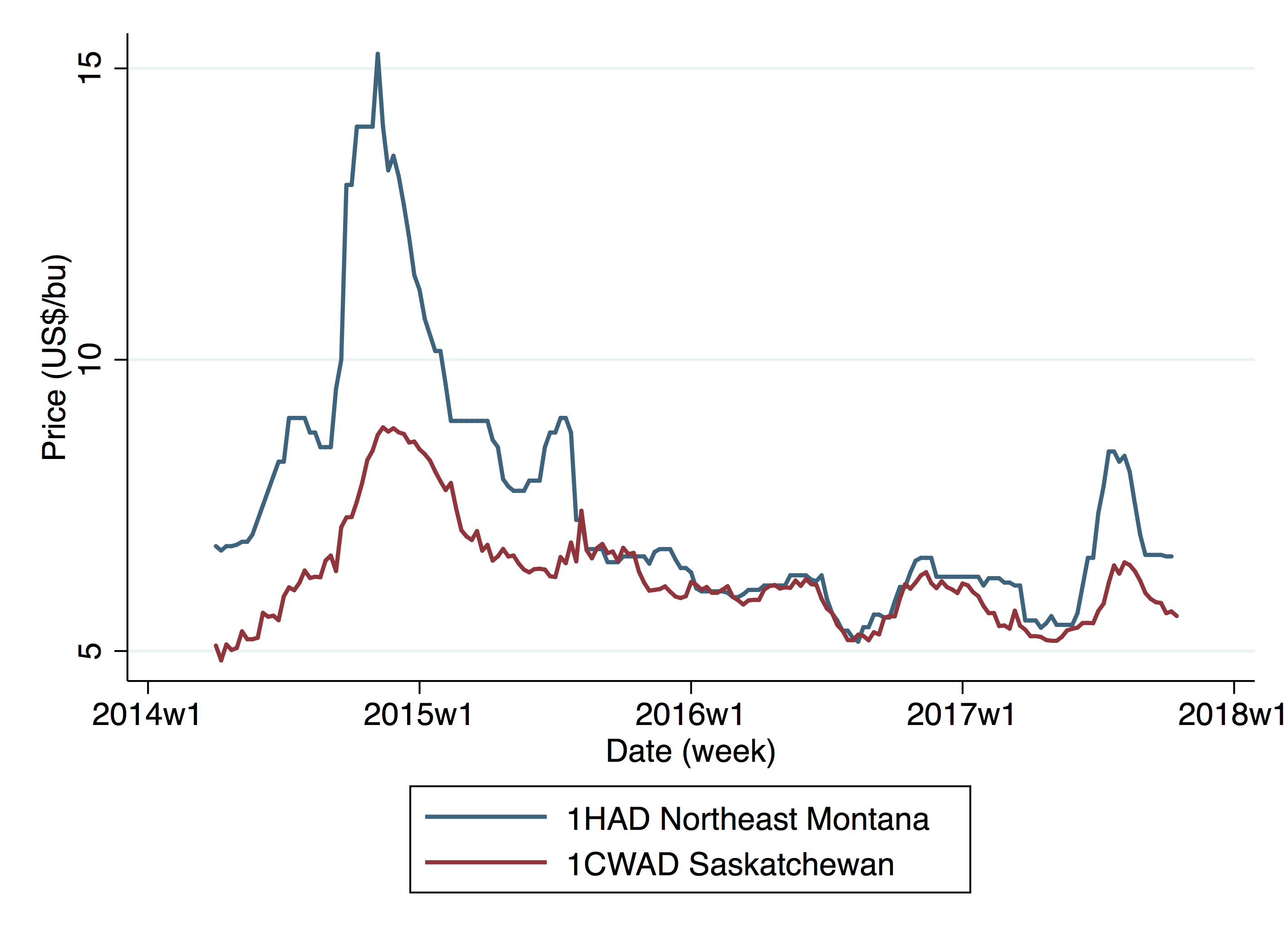

Existing barriers to US deliveries into the Canadian grain handling system do not necessarily mean that prices receive by US growers would be higher if those barriers were removed. Graphs below show Canadian and US prices since 2014 for benchmark grades of hard red spring and durum wheat, expressed in US dollars per bushel. Over the last four years for which we have comparable price data, US and Canadian prices move closely together and Canadian prices have never been significantly higher than US prices. When Canadian prices exceeded US prices, differences have been small and short-lived. This suggests there are few opportunities for US growers to profit by delivering to Canadian elevators. Instead, periodic differences in price incentivize Canadian growers to deliver to US elevators. However, even high levels of imports from Canada (shown above) could not narrow the large price differences between Canadian and US elevators seen in 2014-15.

Since Canadian prices are generally below US prices, Montana farmers would not likely receive higher prices for wheat if grading standards in Canada were relaxed or variety registration requirements eliminated. That said, the absence of significant profit opportunities for US growers selling wheat into Canada does not discount the concerns of growers that trade should be fair and equitable with wheat subject to similar rules of trade on each side of the border. However, it seems likely that harmonizing wheat trade will not bring a significant windfall to US growers or significantly change trade flows.