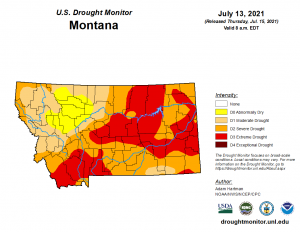

Another major drought is upon us. 95 percent of the western U.S. is now in drought, the most in at least the last 100 years. Montana’s governor recently declared a statewide drought emergency. For the first time ever, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation is about to declare an official shortage on the Colorado River, which supplies most of the Southwest. Last night I reprogrammed my lawn sprinkler system to comply with the city of Bozeman’s new drought watering restrictions.

It’s not a great situation. A bad one, in fact. But just how bad is it? How much harm can we expect this drought to do to agricultural production and rural economies? This is exactly the kind of question that natural resource economists like me work on. It turns out, though, that the impacts of drought are surprisingly hard to find.

One place we can look is rainfall. Too little rain is a big part of drought – maybe the first thing you think of. A lot of studies now have measured how the amount of precipitation in an area affects things like crop yields, agricultural revenues, and farm profits. They generally find that rain is like Goldilocks: too little is bad, too much is bad, somewhere in the middle is just right. But overall, rain doesn’t seem to matter all that much for predicting agricultural outcomes. Temperature, for example, matters much more.

But drought isn’t just about rainfall, and focusing only on local precipitation is going to miss important parts of the story. Drought is about too little water in all its forms, including soil moisture, streamflow, reservoir levels, snowpack, and groundwater storage. In 2018, a team led by Yusuke Kuwayama at Resources for the Future (RFF) decided to use the U.S. Drought Monitor, a composite index that takes all these factors into account, to see what happened during past droughts.

The RFF team found that drought reduces corn and soybean yields, in line with what you would probably expect. But just like rainfall, the numbers aren’t all that big (yields fall 0.1% to 1.2% for each additional week of drought). And surprisingly, farm income and production expenses weren’t affected at all. Farmers in severe droughts often get disaster assistance from the USDA, but that’s not counted in the RFF team’s measure of farm income, so it can’t explain the results.

The research so far seems to say that drought harms crops a little, but not a lot, and it doesn’t really affect producers’ bottom lines. Yet newspaper headlines, and many people’s experiences, indicate otherwise. What gives?

Well, there’s at least one major factor that the research so far has missed, and that’s surface water irrigation. The way these studies work is basically that they take one county in severe drought and compare it with another county in slightly less severe drought. This approach is really good at isolating the effects of drought, making sure that whatever impacts you do find aren’t actually coming from some other factor. The problem is that it also throws out the aspects of drought that aren’t strictly local to that particular county. That includes water levels in rivers and reservoirs, which are often determined by snowpack tens or hundreds of miles away.

So why haven’t economists found large impacts of drought in agriculture? One reason might be that drought doesn’t cause as much economic harm as you’d expect. But another possibility is that we haven’t been looking in all the right places – specifically, we need to do a better job of factoring in irrigation water availability. (My own research is working on this!) Climate change is fueling increasingly severe droughts, so solving this mystery is going to become more and more important.