The meatpacking industry is highly concentrated among a few large corporations. This leads to potential concerns regarding market competition. In perfectly competitive markets, there are many buyers and sellers, so many that no single buyer or seller can influence prices. In the meatpacking industry there are relatively few buyers for live cattle, and relatively few beef sellers to consumer markets—but that does not necessarily mean that meatpackers exercise market power. Meatpacker margins grew dramatically in the spring of 2020 when many workers contracted COVID-19 and plants temporarily shut down. However, increasing margins do not prove that there is market power either.

The meat processing industry has a long history of consolidation. In the early 1900s, Gustavus Franklin Swift and George Hammond developed the first refrigerated railcars to transport dressed beef from Chicago to the East Coast. Swift partnered with Philip Danforth Armour, who opened a large meatpacking plant in Chicago. At the time, Armour’s plant was the largest factory in the world. Henry Ford modeled his manufacturing assembly line after the machine-like process of butchering animals in large-scale slaughterhouses in Chicago.

Initially, no one would transport Swift’s refrigerated railcars. The railroads had invested in stockyards to facilitate transport live cattle to the East coast, and competition from the sale of refrigerated beef might dampen the returns on their previous investments. One railroad conceded though and took his railcars to New York. However, wholesalers in New York refused to buy Swift’s beef. They believed that it was poor quality since it was not “fresh”. Unable to find a wholesale buyer, Swift sold his beef directly to consumers at discounted prices. Once consumers tasted that the refrigerated beef was good quality, Swift was in business. He had vertically integrated the beef industry, from butchering to transport to wholesale. (See Christopher Knowlton’s Cattle Kingdom: The Hidden History of the Cowboy West).

Thus began the consolidation of the beef industry. Cows can be fattened and butchered where high-quality feed is easy to produce, and they can be shipped to consumers all over the country—or the world. The factory-like setting in the original meatpacking plants had large economies of scale. Thus, it was difficult for small plants to compete. It was also highly efficient. However, as we witnessed in 2020, disruptions to this highly efficient system can have major repercussions upstream and downstream in the supply chain.

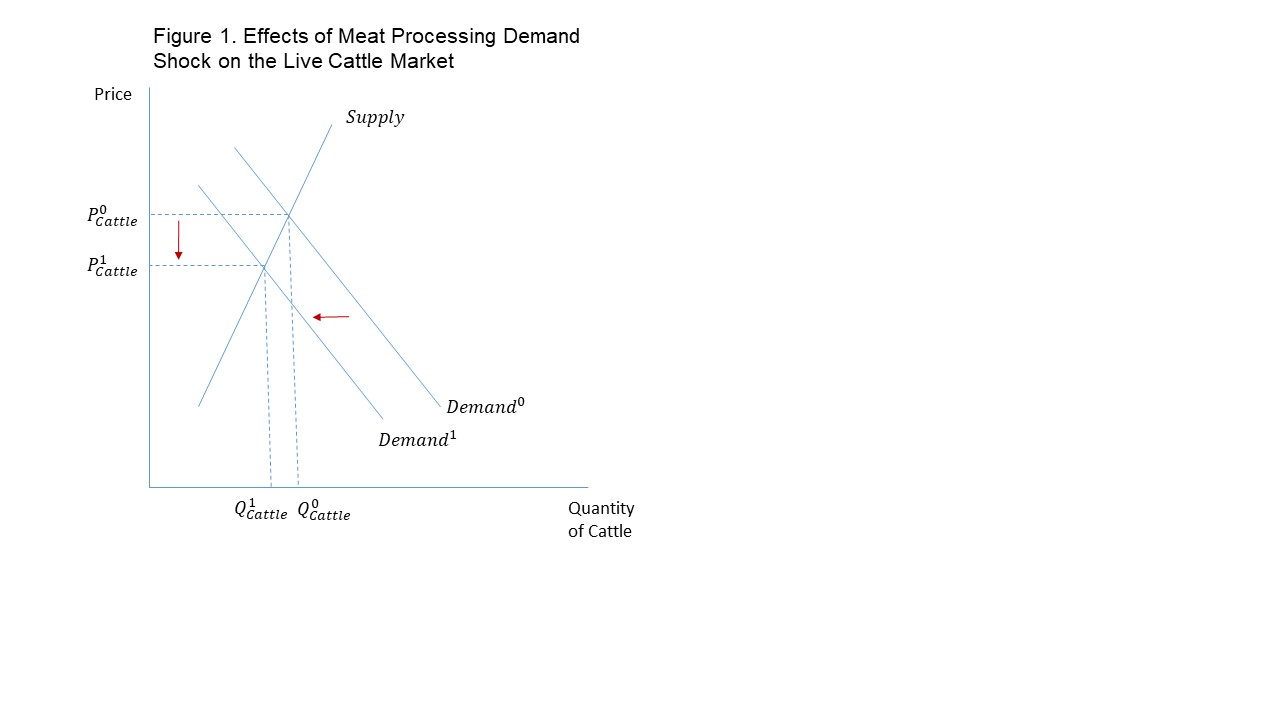

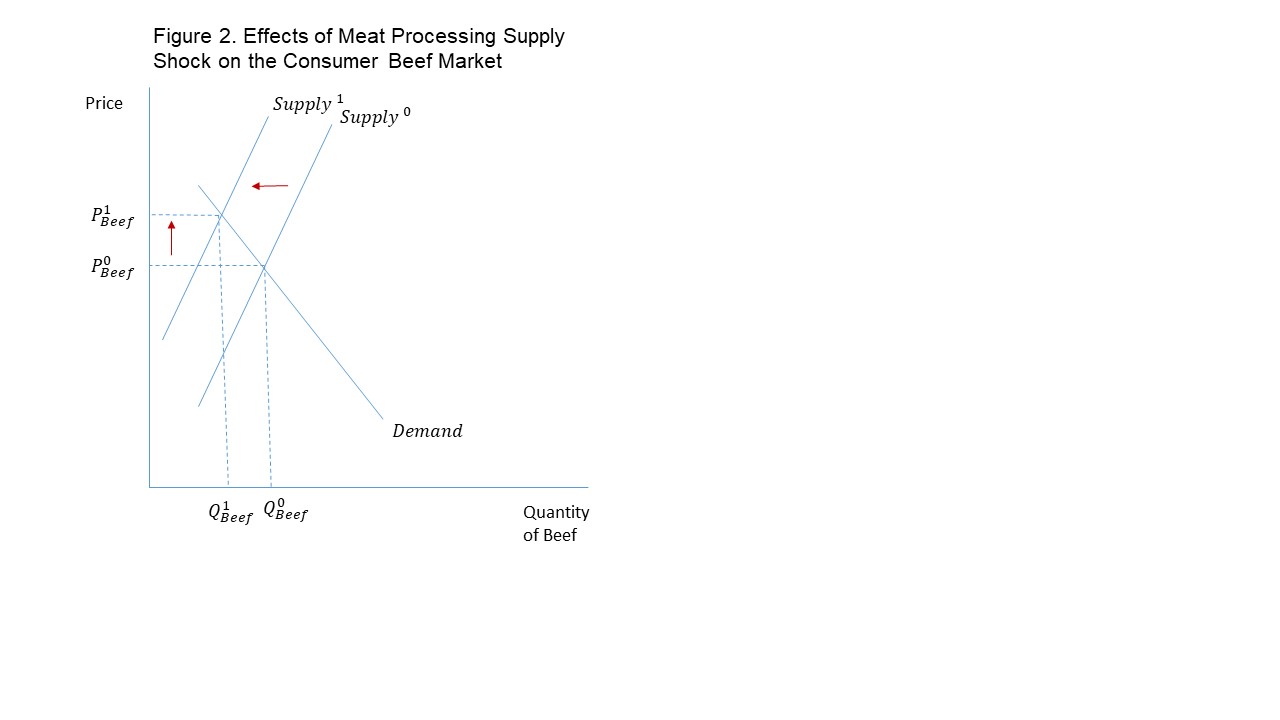

When workers contracted COVID-19 meat processors had to shut down or reduce production. Since fewer plants were operating, slaughter declined and the demand for live cattle shifted inward (see figure 1). Since cattle producers cannot easily adjust their inventory in response to price changes, we say that cattle supply is inelastic. This is illustrated by a steep supply curve. The more inelastic supply is, the larger the price change when the demand curve shifts. Meatpacking plant closures caused the supply of beef in consumer markets to shift inward at the same time, causing beef prices to rise (see figure 2). Thus, the meatpacker had lower input costs (per head of cattle) and higher output prices, and the meatpacker’s marketing margin (output price minus input cost) increased.

We cannot say anything about meatpackers’ profits during the plant closures without additional data. Although their marketing margin increased, the quantity of beef sold decreased. Nevertheless, without making any assumptions about market power, we see that . (See Lusk, Tonsor and Schulz (2020) for a more detailed analysis).

Works Cited

Christopher Knowlton (2017) Cattle Kingdom: The Hidden History of the Cowboy West. Eamon Dolan and Houton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston and New York.

Jayson L. Lusk, Glynn T. Tonsor, and Lee L. Schulz (2020) “Beef and Pork Marketing Margins and Price Spreads during COVID-19” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy