Each year, I read and enjoy critiquing others’ thoughts about what will happen in the upcoming year. This year, I’ve decided to put on old Punxsutawney Phil’s hat and attempt the art of prognostication myself.

Here are four things that I think have a chance to actually happen in wheat markets during 2019, why I think that’s the case, and why I think I may be wrong.

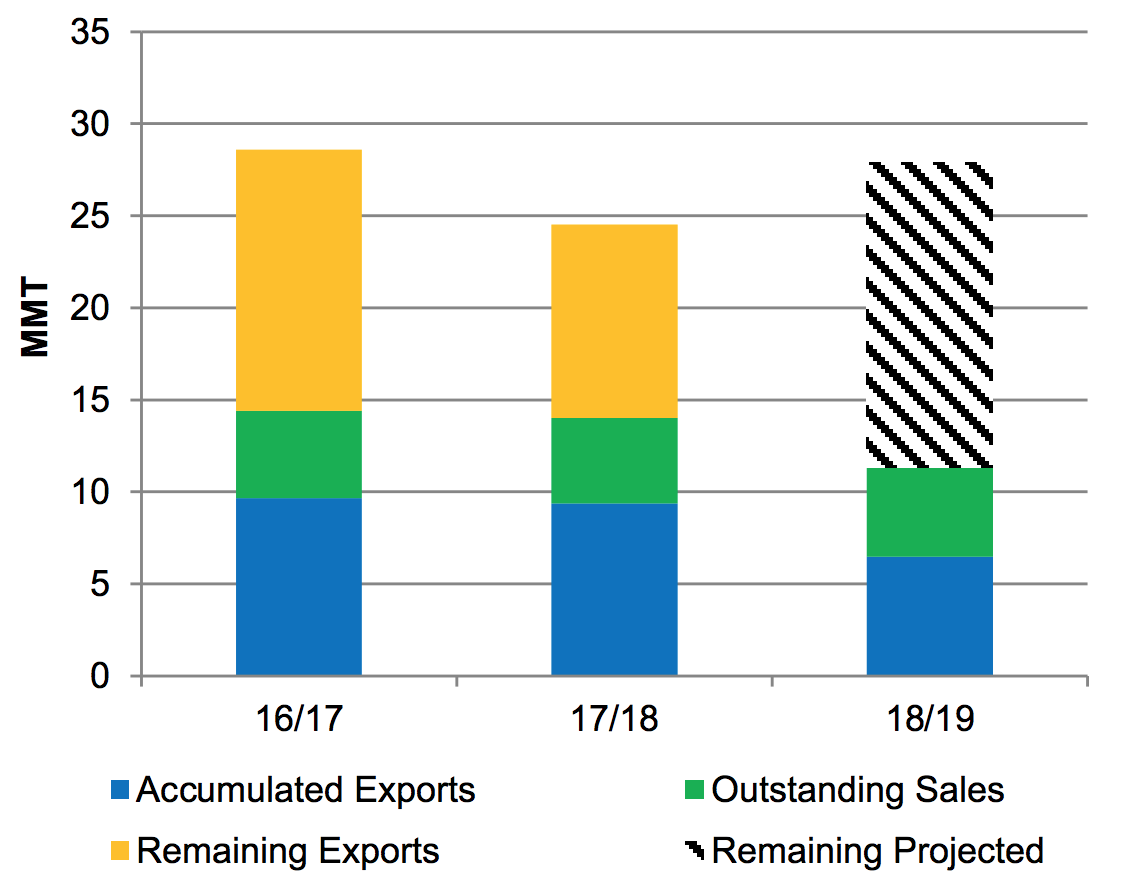

1. Exports of hard red winter wheat will fall well short of USDA projections, but exports of hard red spring wheat will outpace last year’s totals.

Why I think this is correct: In October’s USDA Foreign Agricultural Service’s Wheat Prices Overview, the agency noted that U.S. wheat exports are projected to rebound to 2016/17 levels, after having a relatively down 2017/18 year.

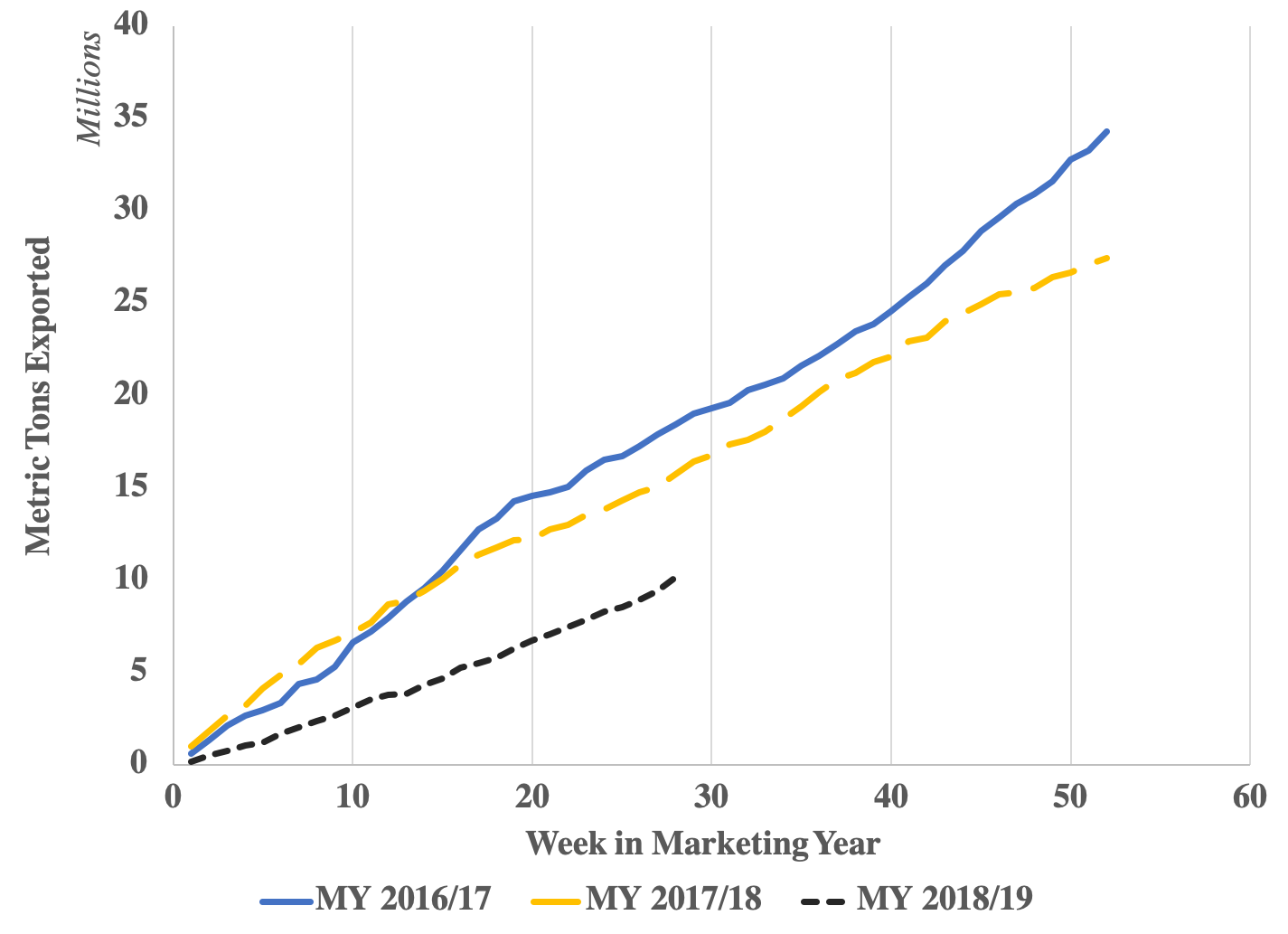

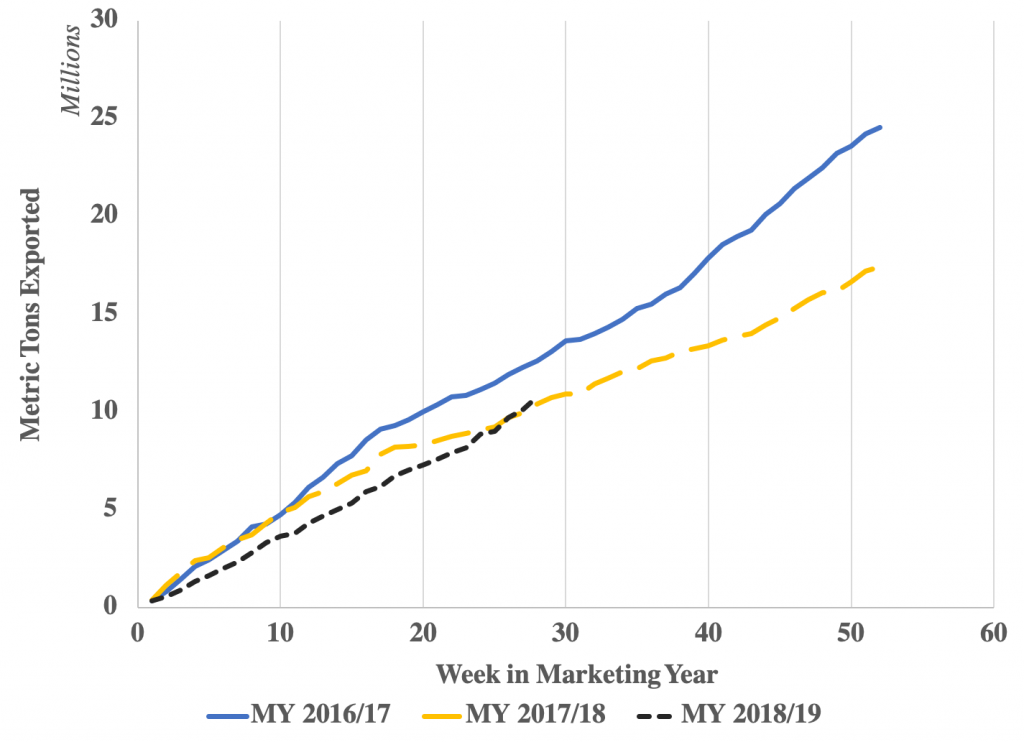

However, it increasingly looks like this story may be true for only only the higher-protein hard red spring (HRS) wheat. As shown in the below graphs of cumulative hard red winter (HRW) exports and HRS export volumes, HRW exports are running significantly below last year’s numbers. However, exports of HRS wheat have been quite strong, outpacing last year’s totals at this point in the marketing year and appearing to be on a trend to potentially reach 2016/17 levels.

U.S. Hard Red Winter Wheat Exports

U.S. Hard Red Spring Wheat Exports

Why I think I might be wrong: In the winter wheat market, the big question remains to be: What will Russia do? The country had a large 2018 winter wheat harvest and set prices exceedingly low in the beginning of the 2018/19 marketing year. However, there is some evidence that Russian wheat supplies have begun to diminish, which may increase the opportunity for U.S. HRW wheat to fill the demand.

On the other hand, both markets may face challenges related to an increasing value of the dollar (I discuss one reason for this below), which would limit the potential for international sales. This may keep HRW exports from reaching their longer-run averages and may limit the upside for HRS exports.

2. Protein premiums in the 2019/20 marketing year will recover due to wetter production conditions in the central Plains and Canadian prairies.

Why I think this is correct: The 2018 production year was particularly good for high-quality wheat. This, in turn, has substantially reduced the premiums for higher-protein wheat. Two important factors (among a number of others) that my research has shown in impacting these premiums are the production conditions in the U.S. central Plains and the Canadian Prairies. If wheat produced in those locations has high protein content, then protein premiums across the U.S. will be relatively small.

Next year, long-term weather projections by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Canada’s Environment and Natural Resource office indicate higher probabilities of average and slightly above-average temperatures and above-average precipitation during May-July in the central Plains and Prairies. You can check out the U.S. details and Canadian details via the links, but the precipitation maps are also provided below.

U.S. May-July Precipitation Forecast

Canada May-July Precipitation Forecast

The increased precipitation and favorable temperatures in the major wheat production areas is likely to result in higher yields but also possibly lower protein levels, due to an often-occurring inverse relationship between wheat yield and protein. If that turns out to be the case, lower supplies of higher-protein wheat would result in higher prices for wheat that does contain the desired protein content.

Why I think I might be wrong: Above-average precipitation and good temperatures are quite good things for crop production. If farmers increase fertilizer rates or the extra moisture increases the uptake of fertilizer by the plants, we could see both higher yields and higher protein levels. If that’s the case, protein premiums may not be particularly high.

3. Overall U.S. wheat prices are unlikely to move particularly far from where they have been during the early parts of the 2018/19 marketing year.

Why I think this is correct: There really doesn’t appear to be much happening that would lead to particularly much optimism or pessimism for wheat prices. While the global demand for higher-quality wheat remains strong and will keep the United States as a consistent supplier of that product for international buyers, continued uncertainty about U.S. trade policy, high stocks of soybeans and corn, and congested transportation systems are likely to place a ceiling on wheat prices. Additionally, in its November market report, the International Grains Council noted that global wheat plantings and production are likely to increase by approximately 1%. This is the first increase in wheat plantings in five years, which may further limit wheat price rises in the early parts of the 2019/20 marketing year.

Price projections posted by the USDA Office of the Chief Economist and the Food and Agriculture Policy Research Institute also indicate that prices are likely to remain flat. The two most recent reports forecast average prices to remain between $5.10 and $5.20 per bushel across all wheat classes.

Why I think I might be wrong: In general, price forecasts are almost always incorrect or, at the very least, imprecise. However, planting decisions in the Midwest and central Plains may add downward pressure on wheat prices. If the U.S.-China trade dispute continues deep into next year, producers who switched away to corn and soybeans in the 2000s and 2010s may choose to return at least some of those acres into wheat production. While I don’t think there is a large chance that this happened this year, protracted uncertainty about international oilseed and course grain trade may change incentives.

4. Interest rate increase are likely to maintain the dollar’s strength and could reduce demand for U.S. agricultural products.

Why I think this is correct: If you’ve been following recent news, you’ve probably at least heard mentions of the U.S. Federal Reserve implementing policy to raise key interest rates, and that this policy is likely to continue over the next year. These policies are highly-researched and are never implemented haphazardly, and their intent is to balance the U.S. economy’s ability to maintain growth without overheating too much (which would lead to high rates of inflation).

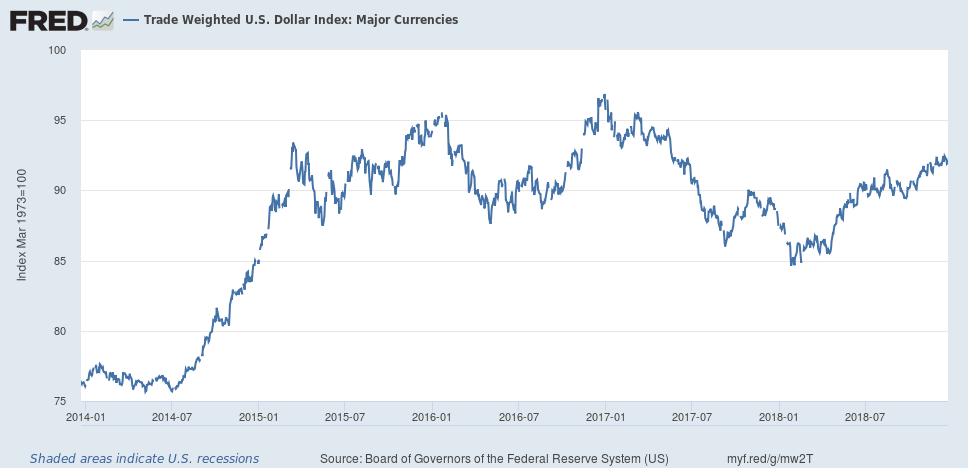

However, one well-known indirect outcome of higher interest rates is the strengthening of the U.S. dollar relative to other currencies. The intuition is that higher interest rates encourage foreign investments into the United States, which increases the demand for U.S. dollars and raises their relative value. The figure below shows that the U.S. dollar has increased over the past year relative to numerous other major currencies, and higher interest rates may aid in future growth.

Trade-Weighted U.S. Dollar Index

In general, this is okay (and quite good for U.S. consumers, who now have higher purchasing power). However, as I wrote in an earlier post, a higher U.S. dollar value is not particularly good news for the U.S. agricultural sector. When the U.S. dollar becomes more expensive to buy, trade partners may turn to other countries (with relatively cheaper currencies) for procuring grains and other products.

Why I think I might be wrong: While the Federal Reserve can always change its mind in light of new information and findings, even if it does continue course and increase interest rates, the impacts on a specialized agricultural sector (i.e., higher-quality wheat) may be limited. This is especially the case if production of higher-protein wheat is limited in 2019/20, making the buyers of such wheat relatively insensitive to price changes. That is, these buyers may be willing to take on the additional costs of a higher-valued dollar in order to acquire the differentiated product.

I’ll revisit my prognostications throughout the year, but I look forward to you weighing in about which one of these you agree with and which ones you think I got completely wrong.

(Photo by Elvert Barnes is licensed under CC BY 4.0)