Here in the DAEE, we are getting excited for Celebrate Ag Weekend and our annual Fall Conference. I love Fall Conference because I see people I don’t see otherwise during the year, I get to hear updates and forecasts from colleagues, and we bring in exciting speakers. This year we’ll be tackling themes of climate change and its effects on Montana’s resources and agricultural production. Land resources will be a strong focus—Paul Jakus, our keynote speaker, and Rich Ready from the DAEE will be presenting on public lands. My focus will be on private Montana ag land values.

Here’s a preview of what I’ll be talking about. Thoughts, ideas, and questions are welcome.

The last several years in Montana have seen extreme market challenges. The cattle market has tumbling back to historical averages from historical highs and the global grain glut brought down prices on the crop side. Those issues have been coupled with weather issues that have added further complexity—wildfire and drought in some areas, flooding and hail in others.

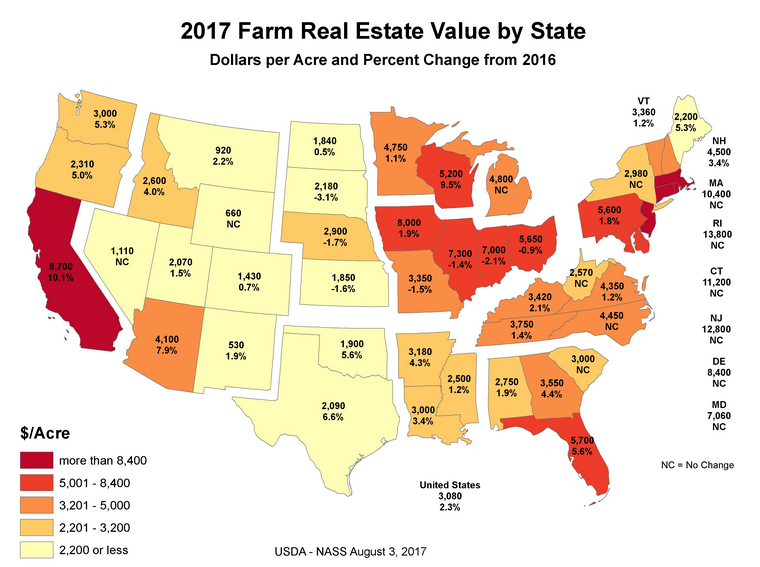

USDA NASS has released the latest information on land values and lease rates over the last couple of months. The average farm real estate value climbed last year, by 2.2%, nearly matching the U.S average rise of 2.3%. With inflation, we are about even with last year.

Average lease rates in Montana fell slightly—from $32 to $31.50 per acre for cropland and from $6.60 to $6.30 per acre for pasture land. Lease rates adjust more quickly than property values so it isn’t surprising to see some decline here but not in the land value stats. Still, I’ve had a number of questions about why they didn’t they fall off more. These are declines of between 1.6 and 4.5%, and there have recently been news reports of Montana ag revenue declining in much more dramatic percentages.

Why don’t the numbers match each other more closely? There are a few reasons. A couple I think are particularly interesting:

- Farmland values are a function of both the current and future returns to holding that land–like any other investment.

This might seem obvious when thinking about land sales values, and perhaps an odd concept when thinking about annual rental rates. But rental rates and land values tend to move together. What this means is that even though ag revenues are currently down, future (evidently relatively hopeful) expectations of revenue may be pushing land values up.

- Returns to agricultural land might not actually be from agriculture.

There are a number of amenity values that have been associated with farmland — scenic beauty, recreation, wildlife habitat, etc. Another key driver is development potential, which is highlighted in a 2014 article from the American Journal of Agricultural Economics. If I owned a farm near somewhere people want to live—for example, near the real estate explosion of Bozeman—I could potentially sell it to someone who would develop it as housing or something else. If I held that card, I might ask for a higher rental rate.

I’ll be talking more about the drivers of Montana ag land values, using some data from local farmers and ranchers on November 3. Hope to see you there!