Last week, I was in Great Falls for the Montana Pulse Day. The Northern Pulse Growers Association (NPGA), the organization representing pea, lentil, and chickpea growers in Montana and North Dakota, hosted the event. It was a great meeting with top notch speakers addressing a packed venue. (The picture below shows half the room!)

Full house at the NPGA Montana Pulse Day! Thankful to all our pulse producers for their tremendous support! pic.twitter.com/K3tXq0LbkN

— Northern Pulse (@peasloveharmony) November 30, 2016

There is tremendous optimism about pulse crop production among farmers. I had the pleasure of moderating a farmer panel discussion where the attendees could ask questions of a set of experienced growers who serve on the NPGA board of directors, including past president Beau Anderson. Both the panelists and the audience confirmed that pulses are the bright spot for Northern Great Plains crop producers amidst an otherwise down outlook.

Why the enthusiasm for pulse crops? Pulses can have significant agronomic benefits when grown in rotation with cereal crops like wheat, durum, and barley, improving soil health and reducing fertilizer expense. Montana State University research has shown these agronomic benefits can lead to higher profits, but only if there is a market for the pulse crops growers have harvested. At the end of the day, pulse prices have to be high enough relative to competing crops.

Considering the pea-wheat price ratio

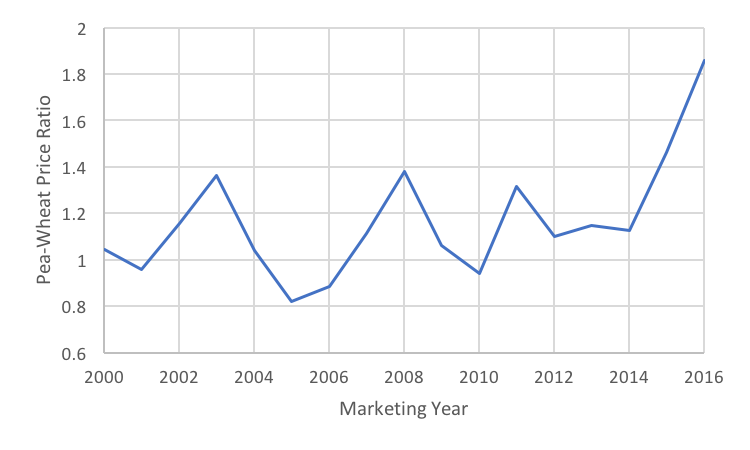

For 2015 and 2016, pulse crop prices have been especially high compared to cereals, at least relative to historical data. The graph below shows the ratio of the marketing year average per-bushel prices received by Montana farmers for peas relative to winter wheat from 2000 to 2015. A higher ratio signals that growing peas is likely more profitable than growing winter wheat. In 2015, the ratio was 1.46, the highest level observed since 2000.

For the current 2016 marketing year, the pea-wheat ratio is even higher. We don’t yet know the average price received by farmers for this marketing year (which doesn’t end until next summer) but using current cash prices in Montana of approximately $6.50/bushel for peas and $3.50/bushel for winter wheat, the pea-wheat price ratio is about 1.85. This is an ahistorical imbalance in pulse prices relative to cereals. Generally, such imbalances do not persist. Absent some structural shift in the marketplace, economic forces bring relative prices back into line.

The current pea-wheat price ratio is due both to relatively high pulse prices and very low wheat prices – both forces have combined to make pulses much more attractive than cereals from a profitability standpoint. While I’ve shown data for peas and winter wheat, this conclusion holds when looking at spring wheat, durum, or barley as alternative cereal crops or lentils or chickpeas as alternative pulse crops.

What does the pea-wheat price ratio mean for next year?

With prices for pulses high relative to cereals, growers may want to switch from cereals to pulses. Pulse crop demand is growing but if pulse acres increase more quickly than pulse demand, pulse prices should fall relative to cereals. Last week, Anton Bekkerman discussed expectations for 2017 wheat acres which are almost certain to be the lowest in over 40 years. The big question is what will happen to pulse acres in 2017. Just how many more pulse acres can growers bring into production?

In Great Falls, I asked the grower panel whether their optimism about pulse crops would translate into more pulse acres on their farms in 2017. What I heard was that for many existing pulse growers in the Northern Great Plains, the ability to increase acres is limited. In most crop rotations, the recommended interval between pulse crops is at least three years. Growing pulses more often increases the risk of yield loss due to crop diseases like ascochyta and sclerotinia.

Increasing pulse acres in the Northern Great Plains will likely mean new growers continuing the conversion of existing fallow acres to pulses. One concern is that yield performance for these new growers may not equal past performance. As your commodities broker or financial advisor is sure to warn you, past performance is no guarantee of future results. Responding to current market signals will require creativity and ingenuity on the part of pulse crop breeders, agronomists, and especially growers. The relative profitability of pulses and cereals is likely to affected by the magnitude of this response and the interaction of grower responses with other global market forces.