As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to take its toll on Montana’s economy, this blog post considers how the crisis might affect the value of farmland, an asset which represents the primary store of wealth for most farmers and ranchers. In assessing how COVID-19 might affect the value of farmland in Montana, it is important to be clear that much uncertainty remains about how the crisis will affect the broader economy and, by extension, farmland markets. With that said, it is still a useful exercise to lay out how we can think about the potential effects of the crisis on the farm sector’s most valuable asset.

Farmland is a non-depreciable asset, and its value therefore reflects discounted expectations over future economic returns to the land, from both agricultural and non-agricultural uses. Despite the differences in what caused the impending COVID-induced recession versus the Great Recession of 2007-09, let’s first revisit how farmland values in Montana were affected during the last major economic downturn.

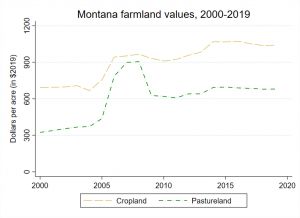

The figure plots the trend in inflation-adjusted average per-acre cropland and pastureland values in Montana from 2000-2019. USDA collects these values every June by asking farmers across the country what their land would currently sell for in an arm’s length market transaction. The Great Recession coincided with far different effects on the value of cropland and pastureland. For cropland, the minor 6% dip experienced over 2008-10 is largely attributable to the decline in wheat demand (and hence prices) during the recession and mirrors the pattern of average National cropland values around the same time. After a sharp increase starting in 2005, pastureland values, on the other hand, declined by roughly 33% in real terms over 2008-11, restoring a large gap between cropland and pastureland values that has persisted over the last decade. The substantial decline in Montana’s pastureland values is at odds with the national trend over this time period, which was essentially flat but masks substantial regional variation (e.g., pastureland values in the Southeast region also declined by 31%). Per-capita beef consumption declined globally during the Great Recession, as cash-strapped consumers sought cheaper options to satisfy their protein needs, and this likely contributed to the large decline in land value experienced by Montana ranchers.

The length and depth of the impending recession brought on by COVID-19, and the extent to which farmland markets will be impacted, depends on several factors, including how long social distancing guidelines remain in place and how long it takes to restore consumer confidence once restrictions are lifted. As noted in a previous blog post, futures markets currently indicate a minimal change in wheat prices and a large decline in cattle futures. On balance, this suggests that cropland values would fare better than pastureland values were these trends to persist for some time. While the African swine flu outbreak last year was looking to be a boon for cattle producers due to substitution away from pork, the COVID-19 outbreak has shrunk demand for beef, as consumers have stayed away from restaurants, consuming more non-perishable grocery items in the safety of their homes.

Another factor to consider is interest rates, which have an inverse relationship with the value of land. Farmland values have been buoyed in recent years by low interest rates, so the recent cut in the federal funds rate to 0% should offset some potential damage to land values. It also bears mentioning that, in addition to the returns to agricultural production (or the “use value” of farmland), farmland values reflect the capitalized future returns stemming from alternative uses of the land, such as residential development. While a housing crisis of the sort that underpinned the Great Recession is not occurring now, it is conceivable that both land developers and would-be movers to Montana may stand pat for some time, which would reduce farmland values at the urban fringe by pushing forward the optimal future conversion time. It seems plausible, however, that the COVID pandemic could shift locational preferences away from housing in denser urban areas, which would yield a more muted (or even positive) effect on the demand for undeveloped land, and hence farmland values, in less dense areas like Montana.

All told, as with many aspects of the COVID-19 crisis, it is far too early to predict with any certainty what effects the pandemic may have on farmland markets. As things currently stand, it appears that pastureland values would be more susceptible to the type of consumer demand-driven economic decline that may be coming. Farmland values throughout the US have been on a multidecade, largely unimpeded, march upward. The extent of any potential reversal of this trend due to COVID-19 will be directly influenced by how quickly the economy regains some semblance of normalcy as the spread of the virus slows. New state-level land value estimates from the USDA, which will be collected in June and released in August, will provide an initial glimpse at how farmers are perceiving the potential repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic.

(Photo by Matt Lavin is licensed under CC BY 4.0)